“We like to think we're not animals, but we are,” says Brian Shapiro, professional development coach, communications expert, and author of the book, "Exceptionally Human: Successful Communication in a Distracted World."

“We act in instinctual ways and you need to understand these instinctual cues if you want to get someone’s attention and persuade them.”

Brian has been helping managers and leaders in the service industry improve their communication skills for over 20 years.

We recently talked to him about how project managers can harness persuasive communication skills to motivate their teams, even without formal authority.

Hidden obstacles

“There's always been the assumption that if you have the capacity to transmit a message to somebody else, you have the capacity to communicate. But there are differences at play with every relationship in the workplace. There are gender differences, ethnic differences, cultural differences... These are all mitigating factors.”

These factors are especially challenging for businesses in the service industry, where success depends on many different people — all with their own personal beliefs and biases — working together seamlessly to drive projects forward.

"Project managers are often caught in the precarious position of managing many diverse personalities without carrying any real authority."

To be successful, you need to form strong relationships with your coworkers. Effective communication strengthens these relationships by building trust and rapport, but hidden obstacles behind our efforts can have unintended consequences, crippling our ability to collaborate and keep projects on track and on budget.

Power dynamics, for example, are a powerful force in every workplace, says Shapiro. “If you're a manager, you have to immediately recognize that there’s a status difference when you're talking to somebody who’s below you. Nothing is going to take that away. People try to ignore it. We talk about the egalitarian workplace, or flat organizational structures. But at the end of the day, someone pays someone else and somebody is going to have the final say in the whole decision-making process. You can’t ignore the impact it has.”

If one of your manager’s requests ever seemed unreasonable, you know what this feels like. You can argue, complain, or get frustrated. But whether or not you agreed with what they asked you to do, the trump card is their authority, and you’re probably going to have to do it anyway.

Project managers, however, have a different problem. In the absence of formal authority, they’re left trying to manage everyone else’s competing priorities. No wonder it feels like herding cats!

So, how can you calm the chaos? How can you overcome these obstacles and keep your team productive and sane?

Let’s start at the beginning.

The "Three Pillars of Exceptional Communication"

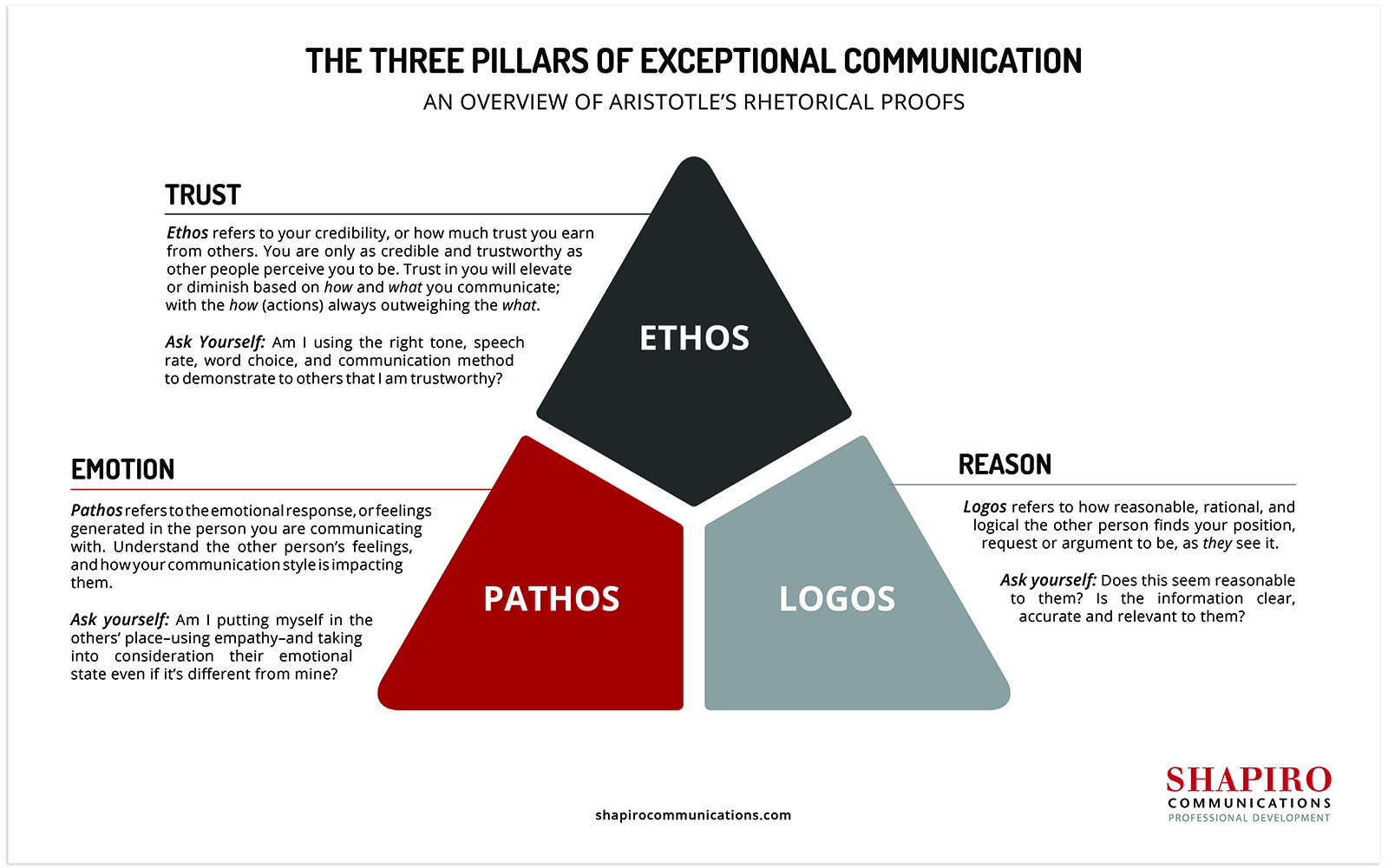

In college, Brian discovered the “Rosetta Stone” of communication success: The Stoic principles of Ethos, Pathos, and Logos, otherwise known as Aristotle’s Three Rhetorical Proofs.

Over time, he would eventually come to call these the “Three Pillars of Exceptional Communication.” In layperson’s terms, they translate to:

Trust, meaning how credible and trustworthy other people perceive you to be.

Emotions, or the feelings generated in the person you’re communicating with.

Reason, which refers to how reasonable, rational, and logical the other person finds your position.

Trust, Emotion, and Reason. These pillars inform every interaction we have because the person we’re communicating with is trying to determine if we are trustworthy or not, reasonable or not, all while having a positive, neutral, or negative emotional experience.

Highly effective communicators know how to skillfully utilize these three pillars to influence others and meet their desired goal.

So, how do you wield these powerful tools of persuasion to manage your team?

6 steps to improving your communication skills

Simply put, in order to influence or persuade anyone else, you need to improve your communication skills. Because you can’t control how anyone reacts, this process has to be about you — not how the other person is or isn’t communicating.

Without formal authority, you must rely on your ability to lead by example, build trust, and help your team members feel at ease.

Here’s how you can get started.

1. Observe and assess your communication competence

Start by observing yourself and how you communicate with others. “By and large, most people probably haven’t taken the time to do an extensive assessment of their own communications strengths and where their opportunities for growth lie. Having that first level of awareness is crucial,” says Shapiro.

“For example, some people might be quite comfortable in conveying difficult information to other people. Other people might find that conveying the same information is so anxiety-provoking that their capacity to deliver it becomes compromised. How they deliver that information only compounds the difficulty of the situation. It’s about having that level of personal awareness and patience with yourself. Look at it from the perspective of bettering yourself.”

Being non-judgmental of yourself is a vital part of this entire process. It’s not about criticizing yourself or shining a light on everything you’re doing wrong. This assessment is meant to help you understand and become better at what you’re currently doing.

“If you don’t have an interest in doing things better, there’s no point in doing any of this stuff. I think everything I provide is on the assumption that somebody actually wants to improve.”

2. Build your tolerance for ambiguity

“Our ability to not know things has been compromised by Google and Siri and Alexa,” says Shapiro. When we have questions, the answers are literally at our fingertips. But Aristotle had a brilliant power of observation — a high “tolerance for ambiguity,” as Brian likes to say. He would observe and discover what was happening in the world around him, without reaching for a fact or reason behind it.

Building your tolerance for ambiguity means being patient and staying humble. It means embracing the idea that you don’t know it all.

"Being uncomfortable is a natural part of the learning process, and that discomfort is not necessarily a bad thing."

In fact, nobody really knows it all, especially about communication. Most of us haven’t had any formal training around how to communicate well. “You took history classes, math classes, and science classes, but no one taught you how to empathize. No one taught you how to listen. Unless you took a public speaking class, or an interpersonal communication class, nobody taught you about all the various theories and concepts around what happens when two human beings interact.”

At best, we had a parent or mentor teach us, or at least our instinct and social mores to guide us. But even those aren’t clearly articulated to most people in life.

3. Listen and learn

People are more likely to do things for other people when they like and Trust them. And while you probably won’t become best friends with most people in your workplace, your ability to cultivate positive relationships with your coworkers is paramount to your success.

To grow these relationships, Brian suggests starting with inquiry. “Get to know who the person is and what their interests are. Discover what they hope to get out of their experience in their role on this project.”

People expect their managers to flex authority. But when you have no formal authority, they can easily dismiss you. “If you don’t have any say over their role, why would they listen to you? But if you start checking in, it builds Trust,” says Shapiro. "Ask a lot of questions, listen, and pay attention. What brought them to this position? How long have they been working here? What skills or expertise do they feel can be of value to this project? Do they feel like we are utilizing you to the best of your capacity?"

Brian advises managers to “be a source of support and inspiration as opposed to simply making sure tasks get done.” When you show other people that you truly value them and their contribution to the success of the project and organization, you build Trust.

“If you think about that, what am I trying to do? I'm trying to increase the level of trust you have in me by helping you feel good about yourself. And you're feeling like a valued contributor to a project because I’m showing a genuine interest in you.”

4. Get comfortable being uncomfortable

Sometimes starting these conversations is easier said than done.

“You have to recognize whether or not you’re comfortable asking those questions,” Brian says. “Can you ask them in a way that allows you to come across as authentic? Are you comfortable making those types of personal workplace connections?”

If not, then you have to focus on improving and begin to deliberately practice. “Set goals for yourself. Try to make a personal connection with someone three times every day, and know it's going to be very uncomfortable each time you do it because it's new.”

This where your tolerance for ambiguity is put to the test.

“You try it again the next day… still uncomfortable. Try it again the next… uncomfortable but maybe not so bad. You try it three times the next day. Suddenly you feel a bit more comfortable. After a week or two weeks or three, you’re able to make those types of connections more often and you’re becoming more effective at what you’re doing.”

“There is no avoiding the pain,” he adds. “If you’re learning to play the guitar, for example, it’s going to be painful. Unless you're willing to tolerate some pain in your fingertips, you'll never learn how to play. The only way to improve is to keep playing and keep pushing those strings until it doesn't hurt anymore.”

5. Be vulnerable and build trust

In the chaos of daily work, it’s almost too easy to say, “Look, this is the company. This is what needs to get done. You’re going to put whatever feelings aside and just take care of business.”

Unfortunately, this kind of power play can have a negative effect on the people you’re trying to motivate.

“Think of each person in your organization as a wellspring of unique experience and knowledge,” Brian advises. “People will want to do more for you if you recognize their unique value to the organization and communicate in a way that puts them in a position of receptivity and ease.”

“If you remain in the realm of Reason and don't begin to recognize peoples’ Emotions, you can make them feel overwhelmed and anxious," he continues. "Those emotions tend to cause our brain to become less receptive to information. Then we're stumbling where we don't necessarily need to stumble.”

“We're not as easily accessible and transparent as we like to think we are, as social media might conveniently have us all believe. We have our defenses. We have our protective layers.”

“Skillful individuals who have highly developed emotional intelligence or communication competencies are able to navigate through these barriers in such a way that the other person starts to willingly put themselves out there because they have a certain degree of Trust in you.”

Building Trust means that both sides need to accept a certain level of vulnerability. People may feel anxious about sharing personal details or emotions with you because they’re giving away something of themselves. And they need to know that in exchange for that information, you’re going to treat them well and trust them in return.

Your team needs to see, through your behaviors and actions, that you have their back and you will continue to support and encourage them, even when they make mistakes.

6. Be positive, helpful, and encouraging

The creative process involves vulnerability and risk. It’s messy, ambiguous, and you often don’t know what the final product will be until it’s done. And once it’s shipped, will anyone actually like it?

If you work in the creative industry, remain keenly aware of how creatives are affected by these feelings, especially when things don’t go according to plan.

“Anything novel carries with it inherent risk. And whoever presents that novel idea is often wedded to it and is going to feel equally at risk,” Brian shares. “Taking into account this vulnerability is an important first step in addressing something that's gone wrong.”

“Let’s go back to our three pillars — Trust, Emotion, and Reason. If someone is vulnerable, their emotions tend to be more negative than positive, so how I present information to them shouldn’t enhance that negative feeling.”

Brian suggests approaching feedback like you would approach a complicated math problem in high school. “Maybe you work it through and come up with the wrong answer. But even though you had trouble in one part of the equation, you’d get partial credit because the rest of your math to come to your answer was actually correct.”

Framing your feedback this way helps engage people in the process of problem-solving. We didn't achieve the result we wanted to achieve. Why don't we go back and look at the work plan or process and see if we can pinpoint and identify where that hiccup occurred?

“Look at it as creative problem-solving to tap into their own inherent creativity,” Shapiro advises. “Let's try and understand. Let's explore why this didn't work out in the way we hoped. Clearly the fact that you came up with a final product or final answer, even if it wasn't the right answer, demonstrated your capacity to see it all the way through.”

By inviting your creatives into the process of problem-solving, you’re able to work together to identify the decision or thought process that led to the wrong outcome. And by doing so, you’re practicing good communication by demonstrating your desire to help the other person learn and improve.

You have to approach it in a way that keeps people engaged and involved, even when they feel vulnerable. Position yourself as part of a collaborative team with the common goal of coming up with the solution to this problem.

“The more you're seen as an advocate and an ally, the more willing people are to engage with you and to follow what you have to say.”

Conclusion

The Three Pillars of Communication – Trust, Emotion, and Reason, provide a strong, proven structure to help us interact with others more effectively at work.

Most notably, we can all be more aware of how other people are perceiving the information we’re relaying. It’s impossible to have an interaction without some form of reaction, so make sure it’s a good one.

This is especially important if you, like many project managers, are tasked with managing others but don’t have a formal leadership title. If you’re in that role:

-

Realize most of us are not the great communicators we think we are

-

Accept that you don’t know it all and relax into ambiguity

-

Step back, observe, and assess how you communicate and how it affects others

-

Listen to individuals on your team and respectfully learn about their interests and strengths

-

Lean into discomfort as you’re improving your communication competencies

-

Be vulnerable and open up to build

-

Trust in others

-

Show your support for their vulnerability and the risk involved in the creative process

-

Provide feedback in a way that’s positive, helpful, and encouraging

-

Above all, demonstrate the type of communication that produces Trust, is grounded in Reason, and promotes positive Emotion

Brian Shapiro grew up in a Los Angeles entertainment industry family, where he witnessed first-hand how communication could be expertly deployed; the spinning of stories and carefully crafted tales that grabbed people’s attention and deeply impacted their lives. The ability to capture and hold people’s attention intrigued him from an early age.

This is not to say that communication came easy for Brian. In college, his first graded speech was barely a C. He eventually began to excel in this class. In fact, it would be this class, his first public speaking class, that would set his career trajectory, and he’s been studying the human communication process ever since.

Learn more about Brian and his work at ShapiroCommunications.com.