Primary Models for CQI in Healthcare

A number of established models can help organizations perform effective continuous quality improvement. Many of those models originated and are still used in other industries. But they can apply to healthcare organizations. CQI models include the following:

- Lean: This model originated with Toyota, a Japanese carmaker. It defines value based on what the customer (or patient) wants, then flows from there. In healthcare, the model focuses on reducing activities that don’t add value, making tasks more mistake-proof, and constantly cutting down on waste to improve the delivery of healthcare. Learn more about Lean project management here.

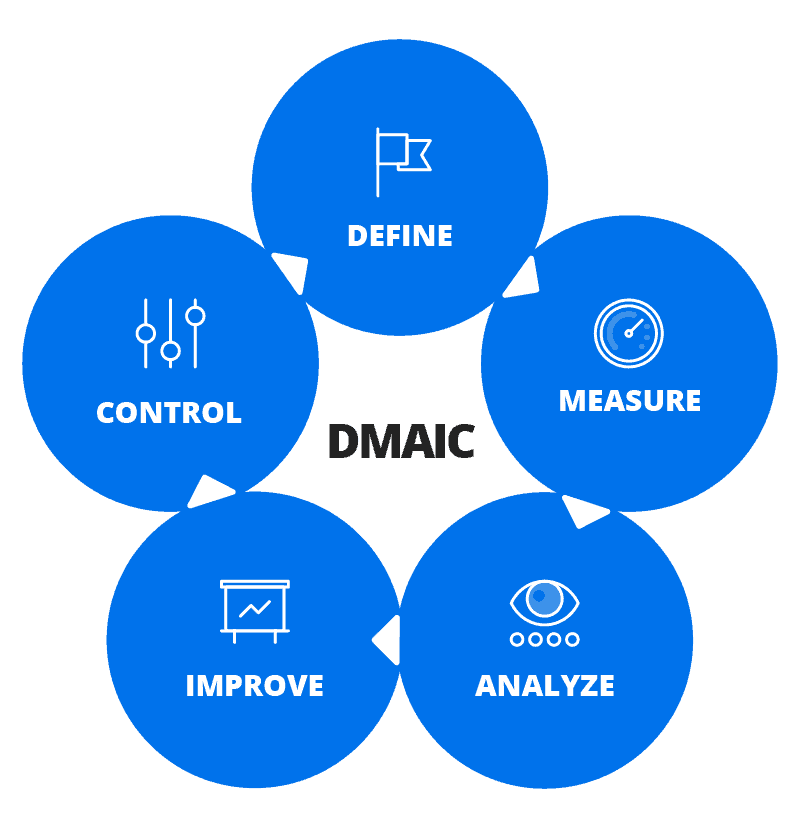

- Six Sigma: This model originated in the U.S. manufacturing industry. It works to improve efficiency by minimizing variability in a process, then finding and correcting errors. As errors decrease, so does variability. Learn more about Six Sigma here.

- Lean Six Sigma: This model combines Lean and Six Sigma.

- Baldrige Quality Award Criteria: Formerly a criteria for an award, this model has transformed into a methodology. It focuses on aligning resources while improving communication, effectiveness, and productivity.

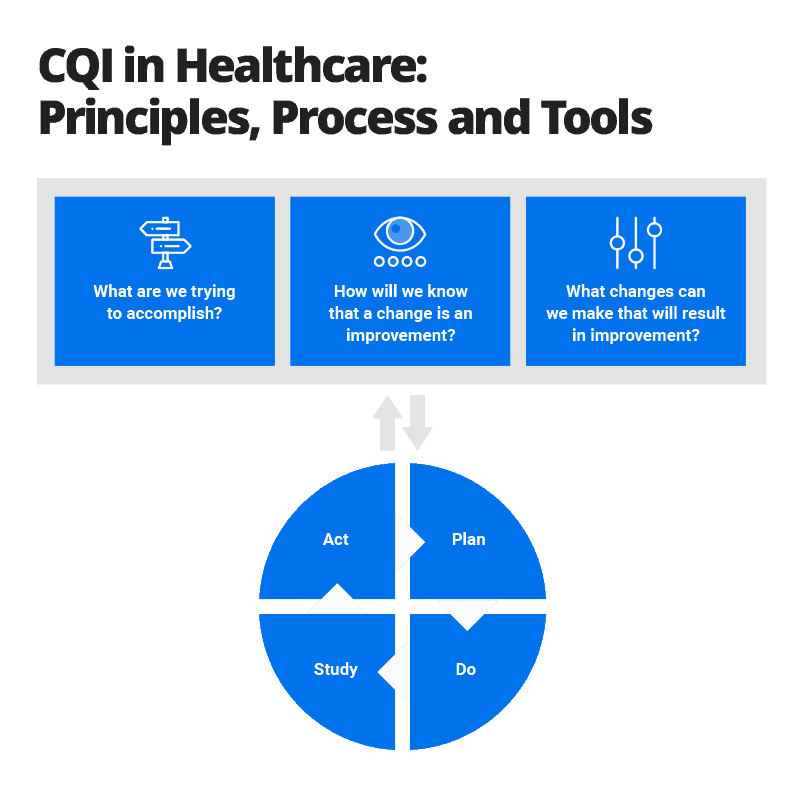

- Plan Do Study Act (PDSA): This model begins by determining the specifics and scope of the problem, determining the changes that should happen, planning for those changes, and figuring out what an organization will measure to determine whether change under way. Then you establish whether any of the changes are positive, adjust if needed, and start the process again. Learn more about PDSA in “A Business Guide to Effective Quality Improvement in Healthcare: Principles, Strategies, Templates, and Metrics.”

- Root Cause Analysis: This method is used most often after an event, usually adverse, to understand the underlying cause. It’s based on the presumption that many human errors occur due to an underlying systemic problem.

- Deming Plan Do Check Act Cycle: This is another term for the PDSA model that includes the name of William Edwards Deming, a pioneer of quality improvement processes.

- Failure Modes and Effects Analysis: This method, part of Six Sigma, tries to prevent errors by identifying all of the ways that they might occur in a process. It then works to change the process to minimize the chance of errors before they happen.

- Focus Analyze Develop Execute (FADE): This model is similar to PDSA and outlines a process to collect data, take actions to improve a process, evaluate whether the actions help, and make needed adjustments.

Versions of some of these models focus on healthcare improvement, including the following:

- The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Model for Improvement: A leading healthcare improvement organization, IHI uses an adapted version of PDSA in its work.

- Care Model: This model creates a system in which patients and healthcare providers have more productive interactions with each other during the care process.

- Health Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (HFMEA): This method, developed by the VA’s National Center for Patient Safety, is a version of FMEA specifically geared toward healthcare.

Different Types of CQI Studies

A continuous quality improvement program often seeks to look more closely at a wide range of processes within a healthcare organization. But a CQI program also focuses on a specific aspect of an organization’s operation. One way to differentiate that focus is to categorize a program as either a CQI process study or a CQI outcomes study.

- CQI Process Study: A CQI process study looks at the effectiveness of a healthcare delivery process. These studies focus on how an organization performs a specific task — often a nonclinical task that may be related to a clinical procedure. Here is an example: how patients are scheduled for and informed about follow-up appointments.

- CQI Outcomes Study: A CQI outcomes study analyzes patient care and whether the organization is achieving expected results. How are patients doing within a set amount of time after a specific procedure? The study establishes measurements that can appropriately assess outcomes and monitors those measurements closely.

Other Ways to Differentiate CQI Programs

There are other methods of differentiating CQI projects. For example, some CQI efforts focus on how an individual patient in a particular condition is treated; others focus on treatment for a group of patients. Individual-level programs and group programs are described below:

- Individual-Level Programs: This kind of program is intended to improve the care for a specific patient. For instance, you may want to determine how to decrease the pain levels for a client through the collaboration of a full medical team: physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, and pharmacists.

- Group Programs: This kind of program is intended to improve the care of groups of patients. For instance, you may want to place patients in certain categories based on their risk of pressure ulcers from laying in a hospital bed for a long period. You can assign categories based on their age, health condition, and other variables. Medical providers then give patients different levels of attention and treatments based on a patient’s category.

The best CQI programs operate as their name suggests — continuously. But some organizations may have financial limitations that affect how often they can conduct CQI projects. The National Commission on Correctional Healthcare, for example, recommends that correctional facilities have either basic or comprehensive CQI programs according to the size of the facility.

- Basic Programs: The commission recommends that correctional facilities with a daily population of 500 or fewer should implement a basic program of at least one CQI process study and one CQI outcomes study at least every year.

- Comprehensive Program: The commission recommends that facilities with a daily population of more than 500 should implement a comprehensive program of at least two CQI process studies and two CQI outcomes studies per year.

Continuous Quality Improvement in Healthcare Information Technology — Especially in Electronic Health Records

You can successfully apply — and get help from — technology used in healthcare for your continuous quality improvement efforts. This is the case with the electronic health record (EHR) that exists for every patient.

An EHR is, in essence, a patient’s “chart” that at one time existed only on paper. It includes information on all recorded aspects of a patient’s health and the healthcare they have received. Recent federal legislation recommended a national goal for the “meaningful use” of EHR technology. That means all medical providers should have easy access to a patient’s EHR and use it to improve healthcare for all patients.

Organizations with a good CQI program can use their EHR information to gain a better understanding of the health of their patients, how certain care helped or hindered their well-being, and how to improve overall healthcare.

What Is Continuous Quality Improvement in Healthcare?

Continuous quality improvement in healthcare is an ongoing process to advance healthcare by always asking “How are we doing?” and “Can we do it better?” The goal is to improve healthcare by identifying problems, implementing changes to fix those problems, monitoring whether the changes help, and making further adjustments if they aren’t getting the desired results.

You might hear other terms in reference to CQI or to programs that are similar to CQI. They include the following:

- Quality improvement (QI)

- Quality improvement consulting

- Total quality management (TQM)

- Clinical practice improvement (CPI)

- Total quality control

Standards and Guidelines on Quality Improvement for Healthcare Organizations

Leading organizations involved with assessing healthcare quality have created standards and guidelines to understand what constitutes good healthcare quality and how healthcare can be improved. Here are two important sets of guidelines:

- The National Patient Safety Goals: The Joint Commission, which accredits most hospitals and healthcare organizations in the United States, establishes and continually updates patient safety goals for healthcare. The current goals include a focus on the following issues: correctly identifying patients; ensuring medicine is used safely; preventing infections; and preventing mistakes in surgery.

- National Quality Strategy: This strategy was first published in 2011 by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It established three overall aims and six overall priorities to improve healthcare in the United States. Priorities included reducing harm in the delivery of care, ensuring that each patient and their family are partners in their care, and promoting effective coordination of care among providers.

The History of Continuous Quality Improvement in Healthcare

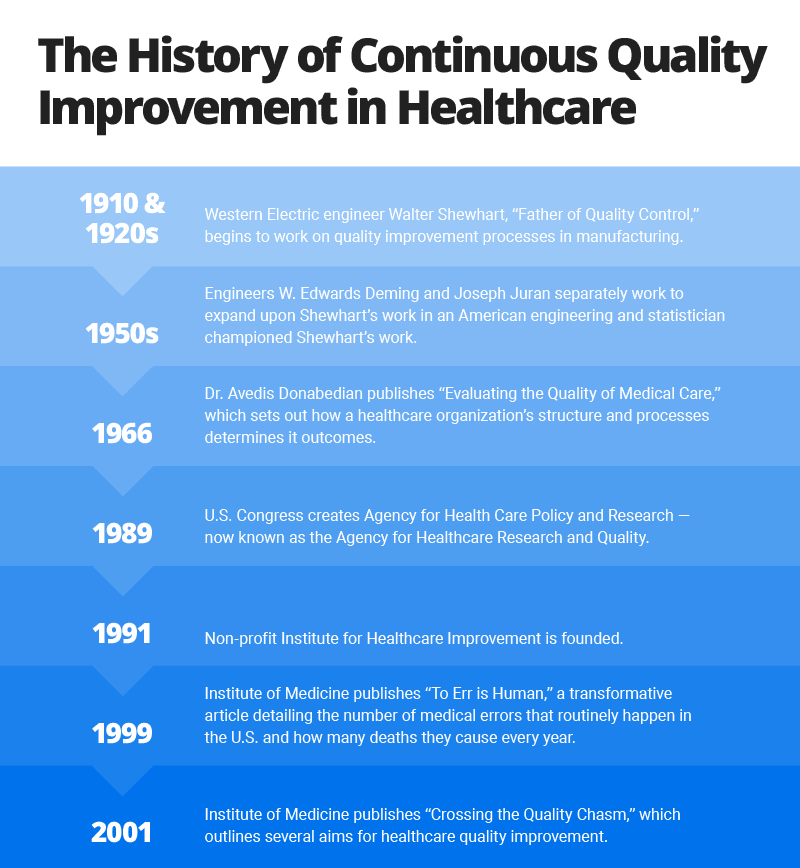

Continuous quality improvement in healthcare is a version of similar processes that began in manufacturing and can be traced back to the 1920s. Some healthcare leaders and academics began thinking more about healthcare quality improvement in the 1960s.

CQI processes were developed further in manufacturing in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as in healthcare in the 1990s. Here are some landmark times and important people in the development of CQI in healthcare.

- 1910 and 1920s: Walter Shewhart, called the “father of quality control,” worked as an engineer in the 1910s and 1920s for Western Electric and Bell Labs, respectively. At Western Electric, he worked in the manufacturing plant to help improve telephone hardware. He began working on improvement processes that became the foundation of quality improvement.

- 1950s: W. Edwards Deming, an American engineer and statistician, championed Shewhart’s work in manufacturing processes. Around the same time, Joseph Juran, an American engineer born in Romania, focused on quality management. He was one of the first management theory leaders to write about the cost of poor quality.

- 1966: Dr. Avedis Donabedian, a physician, published “Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care.” He presented a model for examining an organization’s structure, processes, and outcomes to better understand healthcare quality.

- 1989: The U.S. Congress created the Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research, now known as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The organization continues to focus on research into what works in treating patients, treatment outcomes, and guidelines for best health practices.

- 1991: The nonprofit Institute for Healthcare Improvement was co-founded by Donald Berwick, a pediatrician who in 1986 co-founded the National Demonstration Project on Quality Improvement in Health Care. Berwick is considered one of the most important pioneers of quality improvement processes in healthcare. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement remains a leading nonprofit organization in studying and encouraging healthcare improvement.

- 1999: The Institute of Medicine (IOM) publishes “To Err Is Human,” a transformative article detailing the number of medical errors that routinely happen and how many deaths they cause every year.

- 2001: The IOM publishes “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” a follow-up to “To Err Is Human.” It outlines several aims for healthcare quality improvement.

Read more about “To Err Is Human” and “Crossing the Quality Chasm” in “A Business Guide to Effective Quality Improvement in Healthcare.”

Early Discussion and Analysis of the CQI Movement in Healthcare

Early academic analyses of the CQI movement in healthcare in the late 1990s found that, while the campaign had gained influence, it had yet to show many tangible results.

An 1998 academic study entitled “Assessing the Impact of Continuous Quality Improvement on Clinical Practice” was published in the Milbank Quarterly, a healthcare policy journal. The study authors analyzed 55 continuous quality improvement programs that had been studied and published in academic papers: 42 CQI programs at single sites and 13 CQI programs across multiple sites. They found that the outcomes of care had improved in a number of the cases.

“Particularly important correlates of success appear to be the participation of a nucleus of physicians, feedback to individual practitioners, and a supportive organizational culture for maintaining the gains that are achieved,” the authors wrote.

The authors warned, however, that the success of any new CQI program couldn’t be assumed from the results of the 55 cases. The CQI programs detailed as part of academic studies might have been more likely to succeed, the authors wrote. They couldn’t guess at the number of unsuccessful CQI programs that had never been outlined in academic papers, they wrote.

Another 1998 academic study — “A Report Card on Continuous Quality Improvement,” also published in the Milbank Quarterly — highlighted the progress to that point and the challenges of CQI.

Since 1998, CQI has been much more ingrained in the healthcare system and has produced consistently positive results. However, some of the recommendations and lessons detailed in the 1998 “report card” are still important today, including the following:

- Involve physicians early, not late, in the effort to improve quality. “Use their time effectively and judiciously, and focus on improving practices that are relevant to them,” wrote the “Report Card” authors, David Blumenthal and Charles Kilo. “At least one study found that, rather than alienating them, involving physicians early on facilitated later diffusion of CQI,” the authors wrote.

- Emphasize clinical, patient-oriented improvement, not just cost reduction. “Clinical projects often have the advantage of producing quicker, more easily quantifiable results than nonclinical projects,” Blumenthal and Kilo wrote.

- Invest in quality improvement. Professional expertise and credible data are needed to improve clinical processes.

- Avoid jargon and management-centric language. Discuss issues in concise, easy-to-understand layman’s terms.

- Don’t conduct mass training of staff at the beginning of a CQI initiative. Instead, conduct more focused and intensive training for appropriate staff when a specific project starts.

- Ensure that the healthcare facility’s board of directors participates in the initiative. Getting buy-in from high-level stakeholders is crucial.

To learn more primary methods that can help you perform CQI — including Lean, Six Sigma, and others — along with the appropriate organizational foundation for CQI, tips for successful implementation, and the benefits of CQI to healthcare organizations’ operations, see “A Business Guide to Effective Quality Improvement in Healthcare.”

Applying CQI to Healthcare Clinical Practice

CQI academic researchers have pointed out that applying CQI to clinical practice usually involves three broad categories of problems:

- Overuse: This refers to the use of healthcare services or procedures when the risks outweigh the benefits. “The services that tend to be overused are the prescription of tranquilizers and sedatives and the performance of carotid endarterectomies, hysterectomies, and upper GI endoscopies,” wrote the authors of “Assessing the Impact of Continuous Quality Improvement on Clinical Practice.”

- Underuse: This refers to the failure to provide healthcare services or procedures when the benefits outweigh the risks. “In the underused category are immunization, anticoagulation therapy, assessment for depression, prenatal care, and mammography,” wrote the “Assessing the Impact” authors.

- Misuse: This refers to when an appropriate healthcare service is used improperly. “Common examples of misuse are medication errors and complications or injuries to the patient that are caused by the provider,” the paper’s authors wrote.

Systemic Barriers to Continuous Quality Improvement

You may encounter barriers and challenges with CQI programs, of course. Some of those barriers are due to the inherent structure of healthcare organizations and the healthcare system in the United States. They include the following:

- With scant economic competition in some geographic areas, hospitals and healthcare facilities have little incentive to significantly change how they do their work.

- Physicians can be very resistant to CQI programs — in part, due to concern for their patients.

- Until recent years, medical education has provided little instruction on quality improvement.

- Many healthcare organizations continue to look inward to the desires of their staff, rather than outward to the needs of patients.

- There is a lack of alignment between the quality improvement process and the resources and planning system that would make it successful. “In my experience, when this kind of program doesn’t work, it’s because it’s been treated as a (temporary) tool, rather than a management methodology and a shift in culture,” Larivee says.

- There is too little support or engagement from an institution’s CEO and other top leaders.

To learn more about other challenges to performing good continuous quality improvement, see “A Business Guide to Effective Quality Improvement in Healthcare.”

Healthcare CQI Programs Cover a Wide Range of Clinical and Other Areas

As healthcare organizations have pursued likely tens of thousands of CQI initiatives or more over the past decade, they’ve done the work in a wide range of clinical and other areas. CQI work has been performed in hospitals, blood banks, ambulatory palliative care departments, and correctional institution medical departments, among thousands of other places.

CQI work has also focused on the following:

- Airway management

- Treatment for patients with back pain

- Sepsis rates within a hospital

You can learn more about specific examples of CQI efforts in “The Largest Roundup of Healthcare Improvement Examples and Projects.”

Patient Surveys That Relate to Quality Improvement in Healthcare

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality began developing a patient survey in the early 2000s to assess care for patients admitted to hospitals. The survey was first used in 2006, and results were first publicly reported in 2008.

The survey is called the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). It is administered to patients after they’ve been discharged from a hospital and asks about their experiences at the facility, including the following factors:

- How well medical providers communicated with a patient

- How responsive the staff was to a patient’s needs

- How well medical providers helped manage a patient’s pain

- Whether medical providers offered important medical information to a patient when they were discharged

Results of the survey play a small part in how medical facilities are reimbursed for care of Medicare and Medicaid patients. The results are also publicly available on an HCAHPS website for prospective patients to use in evaluating a hospital. For both reasons, the survey encourages facilities to play close attention to certain areas of patient care and patient satisfaction.

A CQI Project in Healthcare vs. a Medical Research Project: Similarities and Differences

In some ways, a continuous quality improvement project is similar to scientific medical research on a problem. But the two processes are also very different. Here are some distinctions between continuous quality improvement and medical research:

| CQI Projects | Research Projects |

|---|---|

| A CQI project adjusts processes to improve patient care. | A research project tests a hypothesis to add to general medical knowledge on a subject. |

| A CQI project produces findings for a healthcare facility to improve its operations. | A research project adds to general medical knowledge far beyond the healthcare facility. |

| A CQI project uses evidence-based standards. | A research project often tests new methods or standards not yet backed by evidence. |

| A CQI project attempts to make changes that result in patient benefit. | A research project may produce knowledge that has no benefit to a specific patient. |

| A CQI project often follows a method or cycle, such as the PDSA. | A research project adheres to the study design and often includes randomization of patients who get a new treatment versus those who don’t. |

| A CQI project includes most people who participate in a process. | A research project often includes a part of a specific population, with various patients intentionally included or excluded. |

| A CQI project requires a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act release to use a patient’s individual health information. | A research project must identify how it protects a patient’s individual health information and requires specific written consent from any patient to be included in the study. |

| A CQI project might make changes in the process, depending on its findings. | A research project does not change its original protocol; results are analyzed only when the project is finished. |

| The results of a CQI project are not intended to be published in a scientific journal, although they may be. | The results of a research project are expected to be published in a journal or presented to the medical or scientific community. |

| A CQI project is typically paid for by the healthcare organization itself. | A research project might be funded by external agencies or organizations. |

How One Louisiana Medical Center Successfully Executed CQI Projects

Top leaders of the Thibodaux Regional Medical Center in Thibodaux, Louisiana, knew the medical center needed to continuously improve in order to do well.

Chief Executive Officer Greg Stock set up a steering committee that included physicians and other leaders to spearhead the organization’s work in quality improvement. The steering committee, in turn, identified other top physicians and clinical leaders to be part of the work.

The group successfully tackled a number of quality improvement projects, including one to lower the mortality rates of its patients with sepsis, an overwhelming reaction by the human body to infection. Sepsis is a medical emergency and can quickly lead to organ failure and death.

Thibodaux Regional Medical Center leaders estimate that its quality improvement program saves 16 patient lives per year from sepsis. To learn more about Thibodaux Regional Medical Center’s sepsis quality improvement program — and dozens of other quality improvement programs — check out “The Largest Roundup of Healthcare Improvement Examples and Projects.”

Thibodaux has received a number of awards for its commitment to quality improvement, including an Outstanding Achievement Award from the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer and an award for hospital of the year for clinical excellence in pulmonary disease and respiratory care.

Supporting Your Quality Improvement Program and Maintaining Momentum

It’s important that your quality improvement program maintains its momentum beyond the first weeks, when staff enthusiasm might be highest. Here are some important activities and principles to follow to support the program and continually move it forward:

- Track performance over time, and communicate that performance to all employees in easy-to-digest ways. You might track metrics on a monthly or (at a minimum) quarterly basis. You should communicate those metrics and overall performance measures in easy-to-understand graphics; also, share those results widely. To learn more about proper measurements and benchmarks in healthcare quality improvement, see “A Business Guide to Effective Quality Improvement in Healthcare.”

- Communicate your challenges, but also celebrate success. The metrics may show issues that staff should learn about. Moreover, a CQI program can often seem challenging, with staff believing that the organization is not accomplishing enough. That’s why it’s essential to celebrate even small successes when they happen. Minor celebrations for good work break up routines and encourage people to move forward.

Tools to Help with Quality Improvement

To aid in quality improvement work, you can try a wide range of tools, including the following:

- Diagrams that illustrate how a process flows, show the interrelationship among processes, and demonstrate the causes and effects

- Data that’s recorded over time and analyzed on flow diagrams, etc.

- Case studies that illustrate how a CQI process did or or didn’t work

- Survey results that show how patients feel about their care

- Communication tools that allow for sharing a CQI process’ particulars and results with employees

Improve CQI in Healthcare with Smartsheet for Healthcare

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.