Differences between Project Management and Program Management

The term project refers to work with a clear scope and a goal for a specific result or output, while a program refers to a general initiative held by an organization, and is more concerned with its strategic goals.

A program might include a number of related projects, but it usually doesn’t have a specified end date, as does a project. The work of a program will run continuously to help guide an organization.

Thus, project management is the work it takes to oversee project execution on a defined timeline. Program management oversees the overall direction of multiple projects, while always focusing on the organization’s strategic goals.

“They’re related yet different,” says Paula Dieli, a software industry executive and author of Get on Track: How to Build, Run, and Level Up Your Program Management Office. “Program management goes broad, and project management goes deep.

Program management is cross-functional. Project management is function-specific.”

To learn more about the difference between program management and project management, visit our comprehensive guide on how the two compare.

Program Management Best Practices 2021

Experts recommend a range of best practices for managing a program well. Some best practices focus on setting up and starting a program, while others focus on running a program well as it moves forward.

Below, we’ve compiled expert-tested best practices, both for setting up a program and for ensuring the health of an ongoing program.

Best Practices for Setting Up and Starting a Program

- Ensure You Align the Program with Broad and Strategic Organizational Goals: Any program you start must align with the overall strategic goals of the organization.

“Whatever organization you're supporting, you need to understand the goals for that organization,” Dieli says. “And then more broadly, ask, ‘What are the goals for the company?’ Your job is to make sure that what you're doing ladders up to those goals.” - Clarify How Your Program Can Solve a Strategic Business Problem: Even if an idea for a program seems to align with the organization’s strategy, make sure the program is explicitly solving a strategic problem. Don’t embark on a program that isn’t really useful.

- “Avoid creating a solution in search of a problem,” says Randy Englund, a project management consultant, former program manager at Hewlett-Packard, and author of The Complete Project Manager: Integrating People, Organizational, and Technical Skills.

- Create a Program Charter: A program charter will outline the scope of the program and its overall goals. Too often, company leaders and employees only have a vague concept of the goal of a program; sometimes, they have contradictory concepts. The program charter will outline the strategic issue and how the program will work to address it.

- Create a Program Vision Statement: The project charter will lay out the basics of the program. The vision statement is more specific in identifying the ultimate goal of the program for the entire organization. “Have a clear, concise, and compelling vision statement,” Englund says.

To learn more, visit our comprehensive guide on creating a program management plan. - Build a Program Management Framework and Structure: Create a structure and framework through which the program will operate. Some organizations establish that structure through a program management office (PMO), though small and midsized organizations may not have a dedicated PMO. (Read our guide to setting up a program management office.) If this is the case, you’ll still need to establish a framework and structure for the program to succeed.

- Have Clear Goals, but Remain Ready to Adjust to Changes and Realignments: While it’s important to lay out clear goals in your project charter and vision statement, you must also be prepared to adjust and make changes quickly, when needed. Circumstances in the market or in organizational strategies can change, and the program must be able to change and realign when needed.

- Engage Stakeholders and Listen to their Input and Concerns: Engage important stakeholders as you set up your program. Talk about possible program goals, and hear what they have to say.

“Contact each key stakeholder directly, and listen to and act on their concerns,” Englund says.

Englund shares a situation with a top engineer and manager at one of his former companies. The manager’s team was an important part of work for a program that Englund was managing, but he told Englund that the program was not his top priority.

“Right off the bat, the first thing in the meeting, he just kind of threw down the gauntlet,” Englund says, and indicated his team would not be prioritizing in any way the work that was part of the program.

Englund says he had to take project managers and employees within the division aside to understand what the concerns from the manager were really about. “I really had to say, ‘OK, what's the problem?’” When Englund learned about the specific concerns, he did something about it: “I got all the right people together from different divisions and said, ‘Our objective is to resolve this.’ And we did. And when it came back to a system team meeting, [the manager] said, ‘I'm glad I told Randy my problem, because he did something about it.’”

In another circumstance, Englund listened to concerns from a research and development manager who was being resistant to work that the program needed from the manager’s software team. Englund then adjusted the program requirements in a way that dealt with the manager’s concern without hindering program objectives.

“The whole point is, I wasn't arguing with him,” Englund says. “I was listening to him. And I met with him to find out what the concerns were.”

The following table includes common signs of team member resistance to a program and how a project manager can successfully respond to such resistance:

| Signs of Resistance to a Program | What a Good Project Manager Does in Response |

|---|---|

| Team member shows resistance through body language and facial responses during initial meetings. | Notices and finds a way to talk to the person one-on-one to understand concerns. |

| Conflict between departments or divisions on what should happen in a program. | Talks to leaders and team members in each department — in one-on-one meetings or sometimes in meetings with groups — to understand concerns and where a compromise might be reached to move the program forward. It's important that a program manager be seen as objective and not taking sides. |

| Concerns about written objectives or other written messaging that outlines the goals of a program or ways an organization intends to reach the goals. | Holds one-on-one meetings, or sometimes in a small group, with people who have concerns about written objectives. Explores exactly the foundation of those objectives and determines whether language can be amended and still move the program forward. |

| Overall resistance — in meetings, communications, or non-participation on tasks that need to be accomplished. | Has one-on-one meetings to understand any resistance and whether the person's concerns can be accommodated. Then ask for the person's explicit commitment to the program. |

- After Listening and Adjusting, Ask for a Commitment: After you’ve listened to important stakeholders, you may make some adjustments to accommodate those concerns. Then, you need to get the stakeholder’s full commitment to help the project succeed.

“Ask for an explicit commitment: ‘Will you support this program? Will you commit to support this program?’” advises Englund.

Englund says that this step is similar to closing a sale on a potential customer. “It’s a simple question, but a lot of people don’t go for the close,” he says.

Englund says he often has made adjustments to appease stakeholders. “A lot of times, the changes were good ones: they made the program better,” he says. Then he went back to the stakeholders and asked for their support of the program.

But, Englund adds, after listening to continually resistant stakeholders, program managers still might need to make “command decisions to avoid some stakeholders paralyzing a program.”

Best Practices Once a Program Is Underway

- Understand All Risks, and Your Organization’s Tolerance for Risk: You must understand the potential risks to the program’s success, as well as the organization’s risk tolerance. Some organizations are more prepared to accept and deal with risks, while others may have little tolerance for any risks in certain programs. Understand where your organization falls on that risk spectrum, and manage the program accordingly.

- Identify Risks through a Risk Register: Project management also uses a risk register, which is a tool that identifies and logs possible risks to the project.

“The risks in a program are going to be more high-level [than those for a project] — more broad and more cross-functional,” Dieli says. “But the risk register looks the same.”

The risk register will include all potential risks to the program as they arise, as well as whether the risk is internal or external, the probability of the risk, how seriously the risk would impact the program, and how your team will monitor and avoid the risk, or to deal with it if it occurs.

“Focus on actionable risks that can be avoided or mitigated if they occur,” Englund says. - Experiment and Explore with the Program: While you should stay focused on your objective, you can also experiment with new ways to accomplish certain tasks. This might mean exploring work that is unusual for your organization but can still help you reach your objectives.

“Create a culture that encourages experimentation and learning from failures,” says Englund. “The only true failure is a failure to learn.” - Think Ahead and Plan into the Future: Strong program management is about thinking a few steps into the future on behalf of the organization, rather than only focusing on immediate goals.

“A good program manager is thinking, ‘What else could go wrong? What else is needed?’” says Englund.

- “I think the biggest gap between junior and senior program managers on our team is that junior program managers are saying: ‘Here's a problem right now. And here's how we fix it,’” shares Jake Carroll, founder of Create Kaizen, a consulting company focused on personal, team, and organization development. “Senior program managers are saying, ‘I'm going through discovery and learning from leadership and from folks on the ground doing a lot of the actual work. And here's where I see our company, operationally, in 18 months. Here are going to be our major growing pains in order to get there. And here are the solutions to those.’”

Program management teams — especially those in growth-stage companies — must take a step away from the day-to-day and ask: “‘What's our company going to look like in 18 months?’” Carroll says. “‘And if we're going to go from here to there, what are the pitfalls that we're going to run into? What are those hurdles? Where are we going to feel a lot of pain?’”

The goal, Carroll says, is that, “in 18 months, we don't look back and say, ‘Man, if we only just spent a month over the past year tackling these things, we wouldn't be in the place we are today.’” - Give Attention to Urgent Needs: Dr. James T. Brown, former Associate Director of Logistics Systems for NASA at the Kennedy Space Center and author of The Handbook of Program Management: How to Facilitate Project Success with Optimal Program Management, says project managers should be bringing only potential roadblocks to the program manager for intervention; otherwise the project managers should manage the details of their projects.

"On a daily basis, a program manager needs to see the issues he needs to see, and he needs to not see the issues he doesn’t need to see,” says Brown.

For example, Brown says, the program manager may have planned a separate project for that mapping software rollout that involved paid sponsorships from locations called out in the imagery. But as the program and that specific project got underway, it was clear that the clients had not yet worked out the royalties or rights with each individual company, and wouldn’t be able to before the launch of this version of the software. So, the program and project managers have a conversation and decide, along with the client, that the feature needs to be pulled from this program. The project manager can be reassigned to work on another part of the overall release, and knows that when the next update comes to this software in another year or so, he or she will be on-point to take over that task.

The same is true for cost overruns, scope creep, additional unplanned client revisions, and other unexpected realities in projects. As soon as the project manager makes the program manager aware, the program manager should be able to make a call on when to push back, how to course correct, and even if and when to pull the plug on something. This keeps the bulk of the program on budget, on schedule, and on target. That is ultimately what a program manager is responsible for. - Prioritize: Program management teams must work with their organizations to prioritize programs, as well as projects within programs.

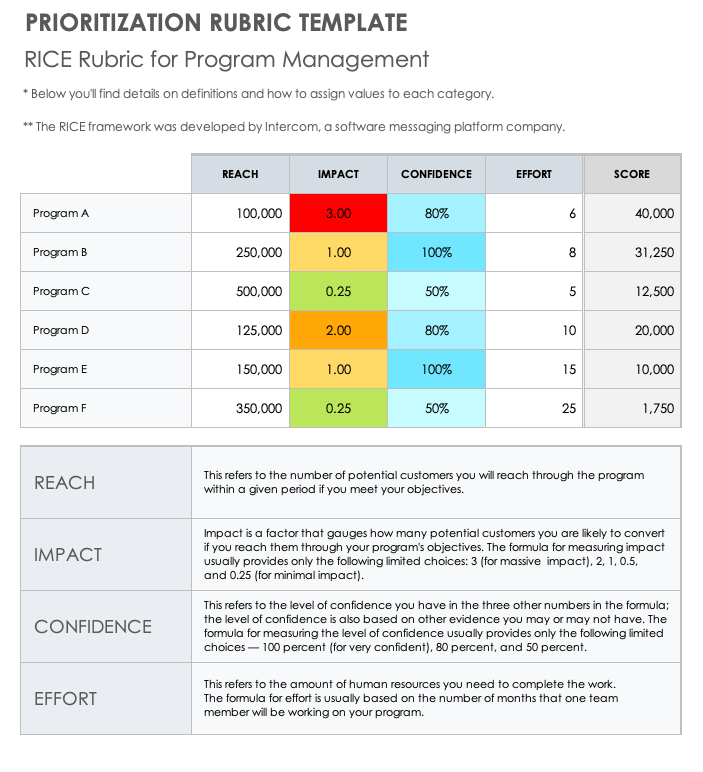

Carroll recommends using a prioritization rubric that helps organizations identify programs and objectives and assess their priority value to the organization. Carroll says he often uses a modified reach, impact, confidence, and effort scoring model (RICE) for prioritization.

“You need to develop a way to show that value rather than just telling people. ‘This is what we’re working on,’” he says. “For certain situations, ask, ‘How many people are we reaching? What is the impact or the hypothesized impact of this thing? What's the confidence that I have that this is the thing to do?’”

Carroll says that RICE can help clarify choices. For some startup organizations, prioritization might include how quickly a project or program can be completed. “We might be working on this thing, because it’s going to provide the most impact. But if it takes 18 months to build, then you may be better off building three or four things with less impact.”

Carroll also recommends a simpler matrix to more briefly assess the value of working on a program. In this model, simply place a potential program in one of four quadrants — or along an x or y axis — based on the program’s value to the business and the effort required to work on it.

Prioritization Rubric Template

Download Prioritization Rubric Template — Microsoft Excel

Use this prioritization rubric template to help you prioritize your projects and programs. The template includes entries for you to assign prioritization scores to a project or program in various categories

- Continually Monitor Results: Carroll says a program management team should always monitor output, outcome, and team health.

“Output is what our teams are working on, and how quickly they are delivering those things,” Carroll says.

Outcome is continually assessing the needs of your customer and what your work is producing. “You want to build something that serves that customer. And then, ultimately, once you deliver that thing, you want to measure what it does, measure how our customers react to it, and learn from it,” Carroll says.

Team health, on the other hand, focuses on how well the team is collaborating and working together, he says. - Continually Assess Your Processes: It’s important to continually assess the utility of your processes. And continually assess whether the overall program management is working, and what needs to change.

“What I tell people — and this is applicable to individual contributors and very much to program managers — is to continually assess things,” Carroll says. “If you’re new, use that to your advantage. Don’t be afraid to question why we do certain things. If you've been here for a long time, take a step back, and try to see yourself and try to act as a new employee, and continually assess the way we do things.”

Enterprise Program Management Best Practices

Not all best practices for enterprise program management are unique to larger organizations, but there are some that enterprise program managers should consider.

Many enterprise organizations will have an enterprise PMO, which may coordinate across the entire organization, or simply across PMOs within one region or one country.

Regardless of if you have an EPMO, the best practices for enterprise organizations are as follows:

- Coordinate and Unify Technologies: Enterprise program management teams should coordinate how the enterprise uses technology and processes in various offices across the globe. Unify the tools and processes as much as possible.

- Coordinate Resources: Enterprise program management teams should also coordinate all resources that are available for program management across the enterprise. Doing so helps the organization with its strategic planning.

- Understand Who Makes the Decisions: Englund points out that the fundamentals of program management are the same among both enterprise and smaller organizations. But to do good work, program managers need to understand the sometimes complicated politics and hierarchy within enterprise organizations.

“Knowing who makes decisions in large enterprises is important, whereas smaller organizations are usually less convoluted and easier to navigate.”

Visit our page on enterprise program management to learn more.

Government Program Management Best Practices

Program management best practices in government organizations are also often similar to best practices in other organizations, but there are some key differences.

Program management best practices specific to government organizations include the following:

- Comply with and Master the Requirement for Greater Documentation: Government programs often have many more requirements relating to documentation and compliance, Dieli says. The program management team will need to keep things “a lot more documented, with more requirements,” she says. “Processes will need to be a little more ironed out. But the skillset is the same.”

- Pay Attention to and Manage Mechanics of Budget Cycles: The continuation of programs in government agencies will always be affected by budget cycles and elections. This can mean some stops and starts more often than in the private sector.

“If your project or program is going across a funding cycle, that’s more challenging,” Englund says. “You have to be aware of those kinds of mechanics of how the government operates. It’s a lot different.” - Manage Requirements of Public Accountability and Concern about Bad Publicity: Government projects and programs are open to public scrutiny, and public demands for change, Englund says. Government workers who manage these programs are also especially sensitive to any possible negative publicity about their projects.

“One of the government sponsor’s success criteria might be, ‘Don’t get written up in the Washington Post,’” Englund says. “They don’t want your program to get negative publicity. And a lot of times, in a private or corporate organization, you don't have that kind of challenge.”

Boeing Program Management Best Practices

The Boeing Company established its Boeing Program Management Best Practices in 1998. Sometimes called “the big eight,” the company still uses the best practices. The best practices range from preparing a proposal to program communication.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid in Program Management

Teams should avoid the following common pitfalls in program management:

- Getting Enamored of Process: Englund says people can become so enamored of their processes that they forget they are dealing with people.

“Your process is not a rule. It’s really a guideline,” he says. “You're there to help facilitate and modify where needed.” One organization, he says, had 63 templates for various parts of program management. “The new people said, ‘How do I do all of these things?’ Experienced program managers realize you only pick the ones that help you.” - Don’t Do — Teach: Program managers and program management staff can and should help organization departments work together. They can teach employees within the organization how to use tools to move the program forward.

That said, don’t let employees assume the program management team will do most of the program work.

“Program managers can kind of be used as a crutch for team collaboration,” says Carroll. “When in reality, a good program manager should be teaching a team how to fish, and not necessarily just bringing them a bunch of fish every day. If you're doing that, then you're essentially limiting what your value is at the company. If I'm just consistently tackling this team's problems and doing a lot of their administrative tasks, I will never gain the ability to step outside that team, step outside that project, and work on some of these higher-level, more horizontal, more forward-looking problems.

“When I'm mentoring a program manager, I tell them — as much as it's counterintuitive — ‘Your job is to work yourself out of a job,’” Carroll continues. “‘Your job is to come into this team, and teach them how to work together and set the expectation that ‘I'm not going to be doing this forever. I'm teaching you how to do it.’ Then I can go to a higher level, look at multiple teams that are all working on the same types of things, and start identifying cross-cutting issues and cross-cutting risks associated with that.”

Streamline Program Management and Drive Results with Smartsheet

From simple task management and project planning to complex resource and portfolio management, Smartsheet helps you improve collaboration and increase work velocity -- empowering you to get more done.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.