What Is a Standard Operating Procedure?

A standard operating procedure, or SOP, is a step-by-step set of instructions to guide team members to perform tasks in a consistent manner. SOPs are particularly important for complex tasks that must conform to regulatory standards. SOPs are also critical to ensuring efficient effort with little variation and high quality in output.

Giles Johnston is a Chartered Engineer who consults with businesses to improve their operational processes and is the author of Effective SOPs. He defines SOPs as “the best agreed way of documenting the carrying out of a task.”

To Charles Cox, a Principal at Firefly Consulting, a boutique consulting firm that specializes in innovation and operational excellence, and a featured contributor to the book Innovating Lean Six Sigma, “SOPs are fundamental to a company’s success.”

SOPs describe how employees can complete processes in the exact same way every time so that organizational functions and outputs remain consistent, accurate, and safe. “SOPs don’t exist in a vacuum. They come from somewhere, and it’s essential that their place in the system be identified. To a large extent, SOPs are the foundation of a company’s operations: If you have no SOPs or inadequate SOPs, your company’s processes are impaired; impaired processes lead to the inadequate execution of policies and so on,” says Cox.

In any organization, all departments — from production to business operations to marketing to sales to legal to customer service — should have SOPs. Defined procedures apply in almost all fields, including agriculture, manufacturing, insurance, finance, and more.

SOPs may be required by regulatory agencies like the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of Transport (DOT), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as well as government legislation like the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX). Standard operating procedures often fulfill voluntary best practices of standards like OSHA Voluntary Protection Programs (VPP), Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL), Six Sigma, International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Practices), and ISO 9001.

Why Do We Need Standard Operating Procedures?

Standard operating procedures, including procedures, workflows, and work instructions, enable good communication and promote consistency in processes and output. SOPs help team members work toward common goals. Managers, team members, and consultants can come together to build processes and document those processes. SOPs, in conjunction with regular training and feedback, guide teams to success.

SOPs are important in clinical research and practice, such as in pharmaceutical processing. In these and other areas, SOPs bolster processes that require triage, segregation of origins, or tracking of cause and effects. In clinical settings, well-prepared SOPs can save an organization from FDA warnings and Form 483 sanctions. The international quality standard ISO 9001 requires companies to document manufacturing processes that can affect the quality of output.

Standard Operating Procedures Remind You and Protect You

Cox explains, “Training requires consistency. We should not be training new employees based on our own idiosyncrasies.” According to Cox, machine-focused enterprises have less variation than human-focused tasks, such as in the insurance or banking industry, where processes center on manual effort, customer service, and human interaction. SOPs can help companies create consistency within procedures.

Furthermore, SOPs provide reminders for people. “When people do things infrequently, they do not recall or do them well,” Cox explains. “For tasks you perform on a daily basis, you may not need a detailed SOP. But the things that are tricky and that you do infrequently may require work instructions. For things that you do infrequently, you may have to retrain every six months or so. When deciding what to add to an SOP, think about how often you do something, how difficult is it, how critical is it, and whether skipping this step leaves you open to problems,” says Cox.

Johnston thinks many people don’t understand the value of SOPs: “I think a lot of people see an SOP as simply a box that you check off to say that you’ve documented a process. They don’t understand that SOPs can be used to audit the process, to look at standards as training tools that ensure recruits are working in the correct way, or even just to guarantee uniformity in the way they conduct business.”

Johnston continues, “People don’t compute that you write these things and actually use them in your business. People think an SOP is something you write and store on a shelf. Then they act surprised when they make mistakes.”

As an example, Johnston describes a client that he helped with instituting an in-person customer feedback process. “My client’s name is above the door of his company,” explains Johnston. “One time, I accompanied my client on a visit to his client. And it was really awkward. The woman giving feedback was embarrassed. She had red ears, a red throat. But she did a great job of giving feedback,” he says.

Afterward, as Johnston and his client consoled themselves, Johnston fetched the company SOPs and showed his client that every learning point from the meeting had already been documented in their quality management system. “I said, ‘When are you guys going to use this document? And live and breathe it?’ My client thought and said, ‘It’s really straightforward, isn’t it?’ I said, ‘Yeah, because you wrote this thing five years ago.’”

How Do You Write a Standard Operating Procedure?

Your task may be to update existing SOPs or to write new documents from scratch. In either case, creating SOPs involves more than just sitting down to write instructions. To write a useful SOP, it helps to have at least a basic understanding of the topic. However, you will also want to get input from others on the processes and on your written drafts. Here’s a step-by-step method to develop standard operating procedures.

- Make a list of business processes that need documentation. If you are a manager, you may consider with your employees what processes need documentation, then compare lists with other managers to prioritize work.

- Choose an SOP format and template. Chuck Cox emphasizes that the needs of the organization must inform the format and there’s no one formatting solution for all enterprises. Consider whether you require a formal package with metadata, such as approval signatures and references, or whether a simple checklist will suffice. A workflow diagram may be an excellent way to provide an overview of detailed processes. You may also find workflow sketches helpful while you capture the information. If necessary, create a template before writing begins or download one of our free, customizable standard operating procedures templates.

- Understand why you need an SOP. Are you documenting a new process or updating and improving upon an existing SOP and process? Whether you’re creating new SOPs or updating existing documents, Cox suggests that you need to confront both de facto and formal SOPs. De facto processes and documentation include what people have always done, along with what they have never analyzed and formally documented. “Whether management likes it or not, there’s a bunch of de facto SOPs floating around, and the insidious thing is that these docs aren’t organized. Someone could be working based on one SOP during the day shift and another during the night shift. If you formalize and get everyone to agree on the best way to do the job, you cut down on sources of variability in ways of doing things,” Cox explains. He says that often teams have never discussed their processes and metrics of output: “Surface and standardize those SOPs according to a format that everyone is amenable to. Make this a team job — you can’t force process on people.”

- Assemble a brain trust to participate in creating documents. Although you may be tasked to write SOPs, you likely won’t have detailed knowledge and experience with every process. Instead, consult the people who perform the processes every day. Documentation that you can use as foundation material may already exist, but SMEs and frontline employees are usually your best sources of content. When you include employees, you also empower them by helping them contribute to the processes and documentation used by the entire organization. In addition, as a manager, think twice about tasking external consultants with writing SOPs. Some pundits suggest that SOPs written in-house by colleagues garner more respect than instructions written by outsiders. Plus, working to create documentation can foster the team spirit that is vital for any endeavor.

- Consider how you will publish and share your SOPs. Documenting your processes is always advisable, but documents help no one if they are hidden or lost. Determine how you will store the documents for easy access by the people who need them every day. Printed sheets in binders may be a good option, or you can choose a digital document management system that everyone can easily access and read, whether onsite or offsite.

- Limit the scope of your documentation. Decide for whom or what you are creating documentation (i.e., tasks, departments, teams, or roles). In addition, determine the limits of the processes you will document.

- Determine your audience and characteristics. Consider the background of your SOP users. A short procedure may work for those who know the process well; others may need detailed work instructions. Also take into account your audience's language abilities — employees with limited English skills may be better served with graphics and photographs.

- Use your template as an outline. Whatever template you choose, think of it as an outline; as you research procedures, you can add details without worrying about the structure of your document. For ideas, see the format and template sections in this article.

- Test your SOPs against the processes. Ask people who perform the tasks daily, those with different levels of knowledge, and those with no knowledge of the tasks to follow your procedures while performing those tasks. The amount of testing you conduct depends on the time and employees you can spare, as well as on the criticality of the process. Ensure that your documents make sense. “I’ve written numerous things in the past as a younger engineer, and I’ve gone back to my instructions and even I can’t follow them!” laughs Johnston.

- Define measures for the success of your SOPs. To understand whether your SOPs serve their purpose, define metrics for them. As Cox says, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” Build metrics into the procedures. For example, as an instruction, “Heat water” is vague. But when you say, “Heat water until thermometer reads 150 degrees,” the instruction is measurable.

- Get the opinion of a seasoned outsider. If you have the option, ask an outsider with knowledge of your business and processes to review your SOPs. Large organizations, especially those that operate under regulatory or other standards, may require official approval and signoff for SOPs. Document reviews may include the quality assurance team and senior staff.

- Plan for updates and an annual document review. Some standards, such as ISO 9001, require regular internal audits. Even if you don’t follow formal standards, now is the time to establish a review and update your schedule for processes and documentation to ensure that your SOPs adhere to the latest regulatory and internal practice regimens. Organizations should review documents at least once a year. Determine now who has oversight responsibilities for the SOPs.

- Assess the risks in the processes. With your formal SOPs in place, look at what could go wrong. “Look at where you are at risk. Which processes have the greatest chance of producing defects? Which production process for an item or service is most likely to injure the end customer and involve the organization in a lawsuit? Work on minimizing those risks. Next, work on the ones that will have a financial impact,” says Cox. “Now, with your formalized processes, you may see risks you couldn’t conceive of,” he adds.

- Finalize and implement the SOPs. To keep track of changes and the location of your documents, decide on a document control process. A version control program can help with tracking document revisions and archiving old versions. Before you share the new or updated SOPs, reflect on your purpose for creating the documents: If you are attempting to standardize behavior or if process updates will result from improvements or regulatory changes, employees probably need training to reinforce the new procedures.

What Is SOP Format?

SOP format refers to the way you structure your standard operating procedure documents. When selecting an SOP format, consider why you are creating the documents: Are they for regulatory compliance or strictly for internal use? There’s no right or wrong SOP format. Use what suits your documentation needs.

For greater ease as you research and write, create or find a template to work with. Your organization may already have SOP templates, or you can find templates online that match your purpose and industry. (To download free, customizable SOP template examples, see the link above to “Free Standard Operating Procedures Templates.”)

4 Structural Approaches to Writing an SOP

The length and format of an SOP depend on how much detail the document requires to clearly explain instructions and purpose. For example, packing instructions for workers in a book warehouse probably differ from those used by an FDA-compliant snack producer. It is crucial to clearly distinguish and label sections to help readers find what they need when they need it. After all, they may most want instructions when they are most agitated by a problem. There are four structural approaches to creating an SOP format:

Checklists:

A simple checklist looks like a to-do list, with precise, numbered steps that you can check off as you finish them. You can print a task list, store it online, or publish it in any format that is repeatable, reusable, or otherwise serves the team. Checklists are particularly powerful when they include measurable results. A simple checklist is a quick way to capture a process without taking on the burden of creating a full manual, especially if you are experimenting with processes that are not yet entrenched. Checklists may be good for small teams and for procedures with few or no decision points. They are also powerful documents for those who are unfamiliar with processes or for processes that require precise adherence to instructions.

When a process includes more decision points, a detailed hierarchical checklist works well. Hierarchical checklists record main processes and the details of subprocesses. For formal documents in which processes may be audited, consider adding distinct, high-level steps that explain the process. As necessary, break high-level steps into individuals tasks that include separate sections for notes on equipment or other information. This way, you can avoid adding information that may obfuscate the processes.

Organization Chart: For complex procedures or the standard operating procedure manual, an organization chart can help users understand the hierarchy of responsibility for processes.

Process Flow Chart: Flow charts provide a visual overview of entire processes and show how different processes relate to one another. Flow charts also supply context for detailed steps in a procedure. Flow charts are well suited to processes with many decision points. More complex versions include swimlane diagrams, referred to as SIPOC (or COPIS) diagrams. Use these for suppliers, inputs, processes, outputs, and customers.

Steps: Common formats for procedures include numbered simple sequential steps or hierarchical steps. Simple sequential steps are ordered, numbered step-by-step instructions for simple tasks that have a limited number of possible outcomes.

Hierarchical steps describe procedures that consist of more than 10 actions, including branches at decision points.

Document Structure

Although documents can be either elaborate or simple, depending on your organization’s needs, most SOPs use at least some of the structural elements listed below:

- Document Control or Meta Information: Each page of the SOPs should include document control information. Often, this information appears in the header and should include the following details:

- A short title or document ID number

- A revision number and date

- The page number, often in the format “# of #.” Page numbers usually appear in the upper-right corner. Some designs include page numbers and other meta information in the footer.

- Title Page: Frequently, the title page of an SOP includes not just identification information, but also approval signatures and version information.

- Table of Contents: A table of contents helps readers find the sections of the document they need. For PDFs or online documents, hyperlinked tables of contents are essential for taking users directly to the desired information.

- Purpose: Very briefly describe your goal in assembling the document.

- Scope: Scope delineates who is responsible for the procedure or what activities the procedure describes. It can also be helpful to describe what is out of scope for the document.

- Terminology, Glossary, Definitions: Define words, phrases, acronyms, abbreviations, and activities that could have ambiguous meanings or that might not be understood by the document’s audience.

- Procedures: Procedures include the step-by-step descriptions of how to perform tasks and can include some of the following sections. Clearly mark each section so that readers who need specific information can easily find it.

- Calibration information

- Cautions to prevent equipment breakage

- Equipment and supplies lists

- Inspection and audit procedures, which are separate from the process SOP

- Methodology

- Records management

- Safety or health warnings

- Reference and Related Documents: This can include other SOPs. List full titles and document numbers, as applicable.

- Roles and Responsibilities: Specify what roles are responsible for performing these activities.

- Appendices: Include any supporting documentation that may not fit within the flow of the procedures. You may add workflow diagrams here.

- Revision History: This often appears in a dedicated block on the cover or on one of the first few pages of the document.

- Approval Signatures: Your organization may require an authorizing officer to sign off on SOPs. This signature block often appears on the cover or on one of the first few pages of the document. For more details on signature blocks, see the link above to “Free Standard Operating Procedures Templates.”

Standard Operating Procedure Templates

With templates, it’s easier to write SOPs because you can concentrate on content without worrying about formatting. The following free, downloadable templates are also customizable for your organization’s needs.

Pictorial Standard Operating Procedure Template

This PowerPoint work instruction template from Giles Johnston emphasizes the use of pictures and short bullet points for instructions. The template includes spaces for two images and a short paragraph or a few bullets for each slide in the deck. You’ll also find additional spaces for author name, date, slide number, and slide title.

Download Pictorial Standard Operating Procedure Template

Simple Standard Operating Procedure Template

Johnston also offers this basic work instruction template. In addition to the meta information, such as author, SOP title, date, SOP number, and issue, this template provides a small space to describe the context of the procedure and a large space to fill with steps. As Johnston says of both templates, “They look pretty basic — until they’re populated!”

Download Simple Standard Operating Procedure Template

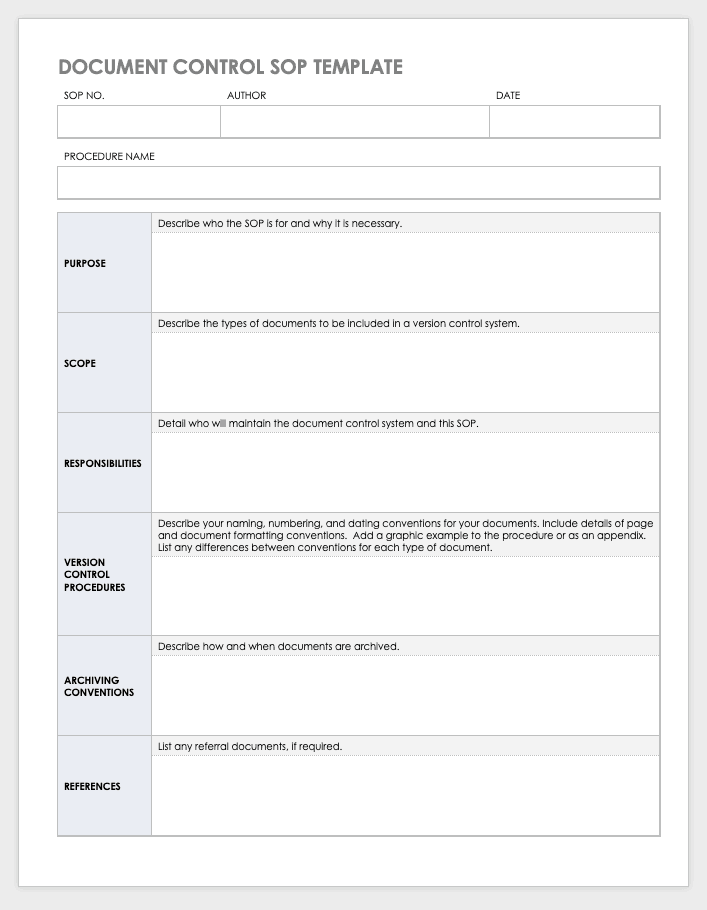

Document Control Standard Operating Procedure Template

When collecting work-related documents, you likely have to standardize a system for formatting, naming, storing, and archiving. This document control SOP template helps you decide what documents to control, as well as how to format, name, number, store, and archive them. This template includes space for discussing who is responsible for document control and for updating the document control SOP.

Download Document Control Standard Operating Procedure Template

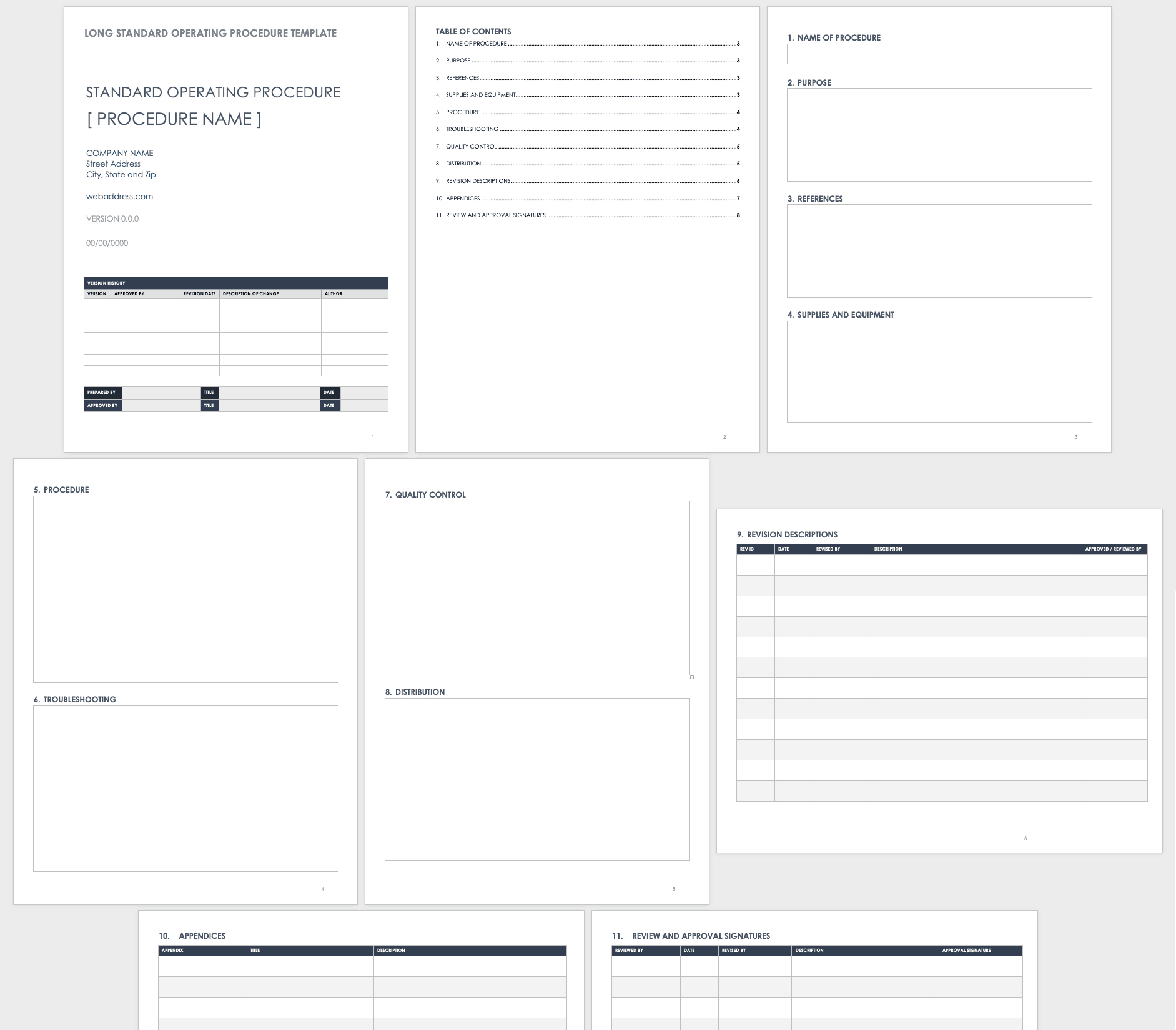

Long Standard Operating Procedure Template

This template for a long SOP includes what many people think of as the SOP itself. In addition to identifying the SOP and describing its purpose, this template provides space to list reference documents, necessary supplies and equipment, troubleshooting information, quality control details, and an SOP distribution list.

Download Long Standard Operating Procedure Template

How to Write Standard Operating Procedures

Charles Cox sums up the SOP writing process this way: “Take the de facto SOPs, come up with a standard, and write everything the exact same way every time. That way, people can get trained and refer to the documents with consistent expectations. Reduce text and increase pictures and graphic; add videos, if necessary. Whatever it takes to move from the world of de facto SOPs or de facto work instructions, do it.”

Giles Johnston sees the need for visual support from another perspective: “A lot of people don’t enjoy writing these.” College graduates may feel more comfortable with writing duties, but most of the workforce does not have the same educational background.

“Not everyone has the ability to translate activities into the written word. If people could get away from worrying about the style of writing and incorporate a few more images, rather than adding endless sentences, we’d probably get a lot more SOPs, written a lot more quickly,” Johnston emphasizes.

Your focus should be on conveying as much information as possible in a small space; the PowerPoint slides and bullet points from the pictorial standard operating procedure template above are a good example of this kind of economical communication. “Short can be effective,” says Johnston.

And make sure that you include all necessary details. “That’s one of the things I see time and time again; people don’t include all the steps,” laments Johnston. “They rush it out, and no one can follow it.” He advises writers to prepare for the “nitty gritty” of step-by-step instructions.

Johnston continues, “I joke with my clients that you have step one, then some magic happens, and you have step two. In reality, there may be 15 steps across a process that you need to capture. People glibly move past them, so it’s crucial to understand all the steps in a process.

“Before step one, maybe there’s a whole loading operation, and before that, maybe there’s a calibration and a maintenance check. You need to capture all that,” Johnston says.

What else should you know to write SOPs with confidence? Here are some important elements to keep in mind:

- Answer These Questions: Procedures are about relationships and controls. Explain what needs to happen in processes and workflows using these cues:

- Who does what?

- How do they do it? What steps do they follow? What tools do they use? How often do they perform the steps?

- What is the result?

- Avoid Ambiguity, Jargon, and Wordiness: Users can get bogged down when following a procedure if steps lack precision or clarity. Here are some SOP writing samples:

- An Example of a Poorly Written Step: Be sure that you use your hand trowel to create a furrow in the soil before you start planting pea seeds.

- An Improvement on the Step Above: Create a furrow before planting pea seeds.

- Use Goal-Oriented Language for Procedures: For example, “Plant beets and onions” is vague, but “Plant 50 beet and 75 onion seeds” provides a measurable goal.

- Designing Procedures: Some pundits say that anything you do three or more times requires a procedure, yet only certain processes need procedures. If the process is simple, routine, and well-known, don’t create a procedure. If the process is a complex one that you perform twice a year, you need a procedure. One caveat is to avoid creating a procedure if you know the process will soon change. SOPs need enough detail (and no more) to ensure consistent performance.

- Graphics and Charts: Good pictures can convey 1,000 words, communicating information in a glance that might take a paragraph to describe. In addition, flow charts, graphs, photos, drawings, and even video can break up long blocks of text. Work instructions may consist mainly of graphics. However, remember to balance visuals with the need to describe methodologies, required tools, and health and safety warnings. Images alone may not be enough.

- May, Must, Should: “May” implies that one has permission to do something. "Must" means that one is required to do something. "Should" means that an act is conditional.

- Pan and Scan: Make documents scannable. Use lists and bullets. Break up long chunks of text with graphics, charts, or pictures that contribute to the user’s understanding of the process.

- Publishing and Storing SOPs: Whether you publish your SOPs in print or online, be sure that they are accessible by managers and employees wherever they work; in this day and age, that includes remote workers and those in the field. People will adhere to processes when documents are easy to find and read.

- Use Correct Notation: Large companies or departments that work with other large enterprises frequently use a common language for documenting workflows. For further information on this topic, see this article on business process modeling and notation (BPMN). Companies often adapt this notation system to their own needs, but if you’re a small shop, BPMN may be more horsepower than you require.

- Write from a User's Perspective: Consider the user’s training and experience level and whether they are native or non-native speakers. Your approach to writing and formatting a document that complies with regulatory requirements likely differs from your plan for a document used by employees on a packaging line.

The Trouble with Classic Standard Operating Procedures

Sometimes, employees avoid SOPs because the documents contain difficult jargon and uninspiring layouts. Thick manuals full of obscure terminology were once staples of engineering and manufacturing environments. Although formal layouts may be necessary for certain standards, such as the FDA, that doesn’t mean procedures and work instructions can’t feature simple language and user-friendly design.

How Do You Write a Procedure?

After you understand the larger process and workflow, it’s time to document the individual procedures. Whether you are an enthusiastic or reluctant procedure writer, do not underestimate the amount of time you need to document procedures. Follow these steps for clear and effective writing:

- Write concise, clear, step-by-step instructions, with details in the order they occur.

- Think of your steps as describing a cause and effect. For example, to boil water, follow these steps:

- 1. Take kettle to tap.

- 2. Add water.

- 3. Set kettle switch to On.

- Use as many words as you need (but no more) to clearly describe steps.

- Where possible, avoid jargon and long or technical words.

- Write in the third person.

- Use active voice — for example, use “Empty the beaker” rather than “The beaker should be emptied.” Also, consider starting each step with an action verb.

- Clearly articulate decision points.

- Create SOPs in the language, style, and format best suited to your organization.

How to Develop Standard Operating Procedure Manuals, aka Quality Manuals

A standard operating procedure manual, known in ISO 9001 as the quality manual in a quality management system, provides a method for collecting your organization’s many procedures in one place. A manual can be as simple as a collection of Microsoft Word documents that you organize into a master document or a traditional binder with pages. “The operations manual provides a handbook for how the business operates day to day,” explains Johnston.

For Charles Cox, “In a very real sense, the information contained in the operating company’s documents impacts the ability of the personnel to meet and exceed expectations. If the documents are not well executed, the information will be difficult to access or understand. Then people will start making up their own approaches, which leads to needless increases in variability and a decline in quality.” Some fields, such as ITIL, have special names for their SOP manual. In ITIL, they refer to the SOP manual as a run book.

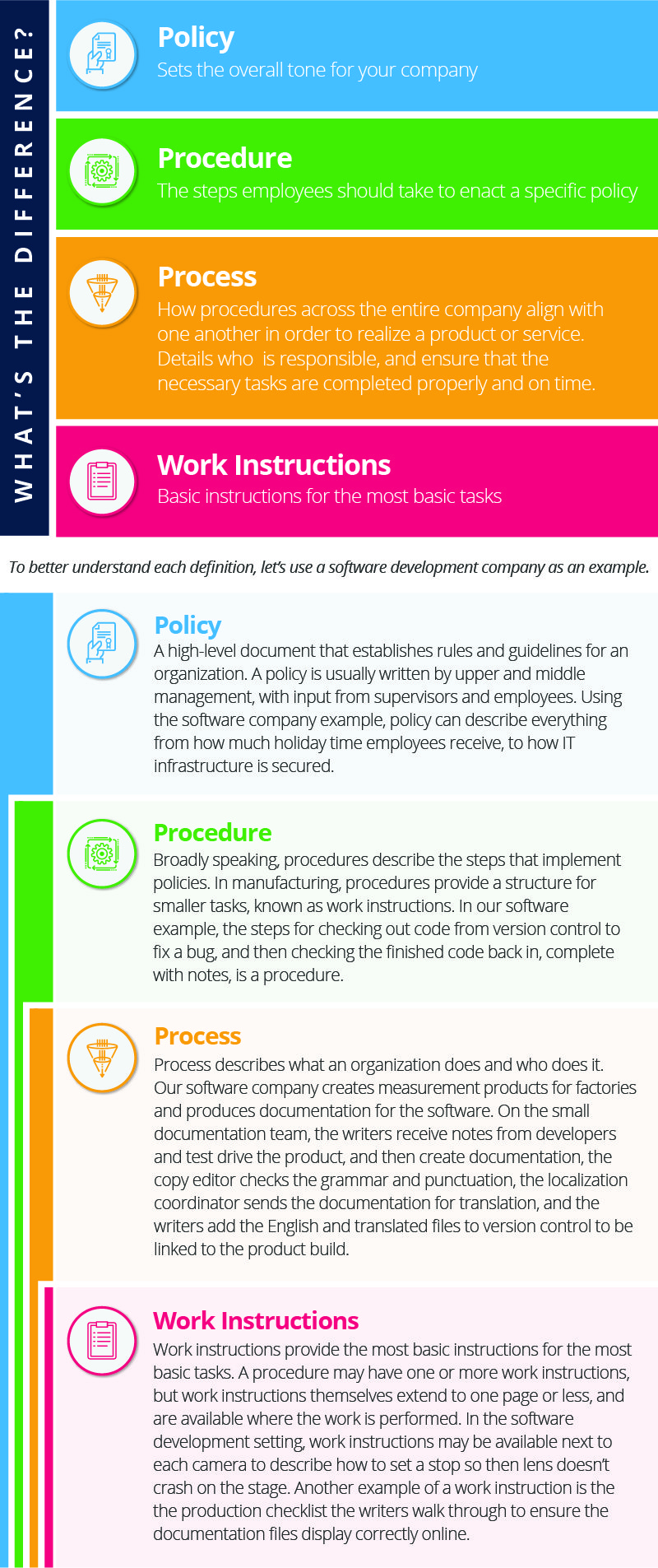

Cox says that an SOP manual can stand on its own, but is usually included in a quality manual, together with policies, processes, procedures, and work Instructions. “How a company splits up these four elements is at the discretion of management,” he explains. “Sometimes, only a few policies that directly impact operations are included in the quality manual, and the remaining policies or all policies go into a policy manual that only upper-middle and senior leadership can access,” he adds.

Alternatively, the quality manual may include only SOPs, inspection procedures, and work instructions. “There are many ways of arranging the documents; the arrangement must fit the requirements of the people who need access to the information. You need a clear understanding of the operating environment before designing the documents system,” Cox emphasizes.

Johnston describes what one of his clients created for their franchises:

- The client mapped out how the system worked as a whole and documented that process in the manual.

- The manual triggered the processes, which were high-level descriptions of what should happen.

- The processes triggered the SOPs.

- The skills matrices referred back to the SOPs for training.

An operations or SOP manual can work well as a repository for procedures, but you must be sure to link everything therein. Johnston cautions against orphans (i.e., pages and procedures that lack linkage to the rest of the document system). Users can stumble across content by accident. “Good linkage is like having a compass. Anywhere you’re dropped, you can find your way back,” he says.

Johnston warns, however, “If it’s hard to find a procedure and you’re busy, you don’t look for it; you just carry on as normal and run the risk of working in an incorrect manner.”

The Hierarchy of Standard Operating Procedure Documents

Procedures form a part of a management system by defining established or prescribed methods and processes. We build procedures from steps, which are the aspect of processes where individuals can introduce variation. SOPs provide the overall framework, while work instructions can change more often. "Procedures provide a description of who does what and when. An SOP characterizes relationships and control measures," says Johnston. Documentation is never a substitute for training.

The following is a hierarchy of SOP documents:

- Procedures: Procedures in SOPs describe processes. You update processes and procedures less easily and, therefore, less frequently than other documents. In the construction industry in many parts of the world, a work method statement appears as a procedure that describes the safest way to perform a task or use equipment. A safe work procedure details processes where a severe problem may occur if users do not follow strict procedures.

- Work Instructions and Checklists: Work instructions and checklists are the detailed how-to documents for new employees or infrequently performed or critical procedures. In addition to word descriptions, pictures of the state of controls (such as switches, screens, and dials) convey information quickly. When writing work instructions and checklists, be sure to include labels and annotations that explain pictures.

- Process Maps: You can first render complicated procedures in a process map. If your SOPs are numbered or labeled, you can refer to the appropriate SOP in the map. For example, if a piece of equipment requires a calibration procedure, you can refer to the procedure in your map, together with any related SOPs. A map may work instead of or in tandem with a large manual that includes all SOPs. Online documentation makes it easy to link maps and diverse documents.

- Skills Matrix: A skills matrix is a grid or table that clearly and visibly illustrates the abilities and competencies held by individuals within a team. Alternatively, a skills matrix can correlate skills and competencies with the SOPs that describe how to complete that process or task. The primary aim is to help in the understanding, development, deployment, and tracking of people and their skills.

According to Cox, the human resource department stores various skills matrices, but for optimum efficiency, managers on the shop floor should keep this information. That way, when technical questions arise, the manager will know who is the in-house expert. In addition, if a team member calls in sick or goes on holiday, the manager will be able to identify capable individuals to perform specific tasks.

“One of the things I find fascinating is that we bring people into a company, sort of train them, and then hope for the best,” laments Giles Johnston. “If we’ve written SOPs, then it makes sense to have skills matrices that refer directly to those SOPs. That way, when someone starts, they can learn the correct way to do things and be judged against that standard; they can know who to ask questions, and we can have effective members of staff that we can track,” he recommends.

What Is the Purpose of Standard Operating Procedures?

SOPs describe your unique business processes and the steps you require to finish those processes in accordance with industry, legal, in-house, and competitive standards. Procedures are step-by-step descriptions, whether predominantly text or graphics.

Standard operating procedures should form the basis of regular training and provide a structure of metrics for performance reviews. SOPs also help you achieve the following:

- Adding value to businesses when they are sold

- Boosting efficiencies and profitability

- Building employee confidence in the safety, efficiency, and regulatory conformity of processes

- Creating a healthy and safe work environment

- Enforcing best practices

- Enforcing schedules, thus saving time and money

- Ensuring regulatory and standards compliance

- Holding employees accountable

- Improving communication (with SOPs, everyone is on the same page)

- Making processes repeatable and ensuring that everyone completes processes in the same way

- Making processes scalable

- Onboarding employees

- Preventing adverse effects on the natural environment

- Preventing process failures

- Protecting employers from potential liability for financial and personnel difficulties

- Providing consistency of process and output for customers and stakeholders

- Providing controls and improvements for known risks that may lead to health and safety problems or nonconformities

- Putting the focus on problem-solving during internal and external disagreements

- Reducing errors and corrective actions

- Unifying a company’s vision and goals

Despite potentially providing rich sources of information, SOPs are often consigned to shelves or hidden in the labyrinth of a file share system. Giles Johnston encourages people to build references to SOPs into business activities: “Learn to tie SOPs to your meetings, not necessarily to training. Usually, some element of an SOP pertains to your meeting and should be reflected particularly in your process meetings to guide people’s thinking. Instead of the SOP being separate from and adjacent to what you’re doing, it’s actually synonymous with what you’re doing.”

Johnston describes a company that included an SOP show-and-tell in its meetings. Senior managers were each given a separate SOP and four minutes to present a precis on how the SOP applied to the meeting. “It was fascinating what people brought back to the table, what they either hadn’t realized or had forgotten,” says Johnston.

He also gives an example of a company in which it previously took a new hire three months to become fully effective at their job. After the company updated its SOPs with enough imagery and clearer articulation and added a skills matrix, new employees became effective in about four hours.

What Is a Procedure Example?

A procedure lists the necessary steps to complete a task, particularly those in a process or cycle. You usually assign sequential numbers to the steps in a procedure (which may also contain substeps). In general, instructional procedures should contain no more than seven steps. Below, we use the example of a procedure for washing dishes in an industrial dishwasher:

- Place a dish rack between the dishwasher and the sink.

- Rinse the dirty dishes and cutlery to remove all traces of food. Scrub resistant particles with the steel wool located in the upper-right corner of the sink.

- Arrange the dishes in the dish rack. Place bowls and cups face down.

- When one dish rack is full, heat the dishwasher water. Press Start and Fill simultaneously. When the water starts running, remove your finger from the Start button, but continue to press Fill until the thermometer needle sits in the middle of the yellow zone.

- Add the dish rack to the dishwasher and close both doors.

- Press Start. If the dishwasher makes a grating noise, press Fill to add more water. The dishwasher stops automatically when done. Use caution when opening the doors, as steam may escape and dishes may be hot.

What Is an SOP in Business?

SOPs detail procedures that you use in your organization to perform activities according to industry and statutory standards, as well as your internal specifications. Procedures include any documents that describe how to perform an action, whether in words or pictures, in print or online.

Why Do We Have Standard Operating Procedures?

SOPs are an important part of a quality management system. Standard operating procedures describe the recurring tasks in a quality operation. Written SOPs reduce errors by detailing the required manner for performing a task. When you update processes and training plans, you should also update the SOPs. When you follow this method, SOPs become a means for notifying employees of process changes. SOPs may be essential for processes that are critical to quality (CTQ).

Storing and Disseminating Standard Operating Procedures and Tools to Help

You need not only to format your SOPs, but also to store them, so everyone can easily access them. Software can help. Business process management software, for example, allows you to store procedures online and track usage from one view. The following are some of the different products you can use to create, review, update, and publish your documents:

- Evernote

- Hackpad

- Pipefy

- Process Street

- SweetProcess

- Wanderlust

- WorkFlowy

Historical Grounds for Standard Operating Procedures

Standardization and SOPs are the outcomes of industrialization, specifically the effort to prevent major accidents. The 1856 train disaster in Pennsylvania occurred when railway engineers in two trains approaching an intersection acted on conflicting interpretations of the rules of the road. The public remonstrations led to the standardization of procedures and what we now know as SOPs. The dramatic example set by the accident showed that unconsidered processes and informal communication cause problems. The example also illustrated how step-by-step procedures clarify processes.

Build Powerful, Automated Standard Operating Procedures and Workflows with Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.