Project Tracking at the Core of Earned Value Systems

To pick the right earned value management system, you need to have a thorough understanding of why earned value management exists and how it operates. Earned value management is based on three metrics:

- Planned value is the cumulative value that was expected to have been earned by a certain point in the project timeline.

- Earned value is the cumulative value that was actually earned by that point in the project timeline.

- Actual cost is the amount of money spent on earning a certain amount of value. When a project’s earned value equals its planned value, it has successfully delivered its scope requirements.

Therefore, comparing planned value to earned value allows a project manager to assess whether a project is running according to schedule. Comparing earned value to actual cost allows a project manager to assess whether a project is running within budget. This integrated comparison of cost and schedule was a big leap forward from project management techniques that rely only on comparing budgeted costs to actual costs.

For example, imagine that you’re a project manager assigned to a project with a budget of $100,000 that is scheduled to last 100 days. On day 50, you look at the figures for project expenditure and see that you’ve spent exactly $50,000. Should you assume that you’re on track to meet both budget and schedule requirements?

The short answer is that you simply can’t know from this information alone. Without using the concepts of earned value management, it’s impossible to assign meaning to project expenditure. Although it may be tempting to assume that half of the project budget spent halfway through the planned project timeline means that everything is going according to plan, this may not be the case.

For example, it’s possible that you’ve spent half of the project budget and are halfway through the planned project timeline, but have only completed a quarter of the work. So while your planned value and actual cost are both $50,000, your earned value is only $25,000.

This means you’ll have to complete the remaining 75 percent of the project work with only the 50 percent of the budget and half the scheduled time remaining. Given the project’s cost and schedule performance record so far, you’re probably looking at some pretty heavy cost and schedule overruns.

Earned value analysis is the most comprehensive trend analysis technique available to project managers. Used consistently throughout the execution of a project, it is an invaluable tool for gauging project performance and suggesting corrective or preventive actions where necessary. The Project Management Institute’s Practice Standard for Earned Value Management (PMI Global Standard) is worth reading for any project management professionals looking to incorporate EVM concepts in their work.

A Brief History of Earned Value Management

Although the concept of earned value management originated in the early 20th century with the work of management theorists Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, it owes its widespread use to implementations in 1960s’ U.S. government programs. In 1967, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) attempted to address serious cost and schedule overruns by using the Cost/Schedule Control Systems Criteria (C/SCSC), an approach comprising 35 management standards for tracking cost and schedule performance in large DoD programs. Although using C/SCSC was more of a financial control tool than an approach to project management, its objectives were the same as those found in earned value management today: proper planning, regular performance analysis based on the use of performance baselines, and corrective action when necessary.

The DoD’s interest in program schedule and cost performance grew in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. The shift was prompted largely by a declining national defense budget and growing public concern about problems with programs such as the Navy’s A-12 Avenger II, which was terminated in 1991 on the basis of earned-value performance analyses. In 1997, after recognizing the benefit of earned value management, NASA stipulated a series of requirements based on earned value management that were applied to NASA contracts going forward.

Outside of the government, the architecture, engineering, and construction industries were among the first to adopt earned value management practices. In 1998, the government discarded the C/SCSC system in favor of more flexible earned value management techniques. Many contractors considered the C/SCSC system overly burdensome, and the ANSI EIA 748-A standard (which was developed by the Government Electronics & Information Technology Association) transferred ownership of the earned value management criteria to the industry. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which mandated disclosures of project statuses and costs by U.S. public companies, also drove the adoption of earned value management techniques to improve meeting disclosure requirements.

In the United States, the Department of Energy, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Transportation, and the Federal Aviation Administration now require the use of earned value management on projects. England, Canada, Australia, China, and Japan also use earned value management techniques.

Over time, earned value management has evolved from a strictly financial tool to a methodology for project management that you can apply to anything - a single project or an entire enterprise - via the use of integrated EVM systems.

Benefits of EVM for Customers and Contractors

Earned value management facilitates and simplifies communications on project performance, making it an extremely useful methodology for customers and contractors alike. The three metrics of planned value, earned value, and actual cost allow for simple yet accurate assessments of cost and schedule performance, which enable better project management overall.

Since earned value management provides real-time visibility into project performance and opens lines of communication, it tends to increase a customer’s confidence in a contractor. Many customers also feel that increased communication gives them greater control over determining courses of action for a project. Corrective action may be necessary if performance trends are poor (more than a few high-status military projects have been scrapped in the past because of poor performance forecasts). Similarly, contractors are also better equipped to identify and respond to performance problems, which also increases customer confidence.

In addition, contractors benefit from at least two other practices related to earned value management. First, the increased emphasis on thorough planning and assessing the value of each component of a work breakdown structure can improve both the accuracy of estimates and the quality of risk planning. Forcing project managers to calculate the value of every project task increases the chances of catching previous errors or oversights made in estimating, and a careful examination of the activities involved in each task may provide insights into previously overlooked risks.

Secondly, earned value management can help counteract scope creep. The methodology is based on integrating the three aspects of project performance: scope, cost, and schedule (the latter two being dependent on the scope). The basic principle that all project work must be assigned value serves as a check on scope creep, since strong practice dictates you must reflect all increases in scope by increases in the total value of the project.

Implementing an Effective Earned Value Management System

We’ll look at the exact calculations involved in earned value management later, but it’s important to note that applying earned value becomes more complex as projects become bigger and more sophisticated. The size of a project will have a bearing on the tool you use to implement EVM. Manual calculations or spreadsheets are adequate if you are learning about EVM or applying it in a small project, but larger projects may require a more complex, integrated system.

EVM tends to be most relevant for extremely large projects such as advanced defense systems or a big construction job. A large project may have hundreds or thousands of activities, participants, and costs. Successfully applying EVM requires software that can execute the necessary processes and work with your other financial and project management applications.

An EVM system should have the capacity to achieve core objectives, whether by formulas embedded in a spreadsheet or EVM software. As you’ll see, the standards and rules can vary, and the tool must be able to adapt to these variations. An EVM system must address the following core objectives:

Relating time-phased budgets with a comprehensive breakdown of project work. The first step in earned value management is assigning portions of the budget to all scheduled project activities. This is typically accomplished by defining the complete scope of the work as a set of mutually exclusive elements via a work breakdown structure, and then assigning value to each of these work breakdown structure components, also known as work packages. Learn more about the work breakdown structure including how a scope of work helps define project activities.

Creating a baseline to evaluate progress and cost performance. You can create a performance measurement baseline after each of a project’s work elements have been assigned value. It effectively tracks expected expenditure over time as a project is executed. A project manager constructs a baseline based on schedule network analyses, using relationships between activities to determine the expected total duration of a project.

Once the schedule is created, match budgetary allocations for each work component to a point on the schedule at which its value is expected to be earned. A key step is defining earning rules, which determine when the value of a task is earned. The simplest earning rule is the 0/100 rule, where a task earns 100 percent of its value upon completion, and no value prior to completion.

Depending on the size of a task, however, you can also employ an alternative called the 50/50 rule. This rule considers half the value of an activity earned upon starting it and half earned upon its completion. A project manager may also use other, similar rules, using ratios such as 20/80.

The purpose of these mixed-ratio rules is generally to provide a more accurate picture of progress. Larger or more complex activities usually require more time to be completed, and assigning earned value only upon completion — while actual costs are continuing to rise — might provide a misleadingly negative picture of the project’s performance.

Based on these earning rules, you can determine the planned value at any point in a project timeline. Therefore, the performance measurement baseline functions as a representation of cumulative planned value over time. Compare the planned value with the earned value to determine schedule performance, and compare the earned value with actual cost to determine cost performance.

Providing valid, timely data to enable proactive project management.

Project tracking is the practice of regularly comparing the performance measurement baseline with the earned and planned value and analyzing any variances. It is often aided by graphs, which help team members examine historical cost and schedule trends, and also forecast future performance expectations.

Earned value management is popular because you can easily interpret cost and schedule performance data and use it as a basis for action. Of course, small variations from the baseline are not necessarily a cause for concern. That said, effective project managers will realize when overruns are turning from anomalies into trends, and will employ remedial measures where necessary.

The Basic Components of an EVMS

An earned value management system usually comprises four distinct - yet integrated - components: scheduling engine, the cost engine, the reporting engine, and the accounting system.

For organizations looking to set up an EVMS, the accounting system is usually already set up, as is the scheduling engine. In such cases, the existing components should remain in place to minimize disruption and the time and effort needed to adopt new systems.

The Scheduling Engine: In general, a scheduling engine is a software tool that facilitates the creation and maintenance of a project schedule and uses schedule analysis techniques such as the critical path method. The project schedule is the basis for assigning resources to project work. In an EVMS, the scheduling engine holds the baseline and the current schedule for the project. It’s imperative that the scheduling engine is closely integrated with the cost engine.

The Cost Engine: A specialized EVMS tool that integrates cost and schedule data for projects. By collecting data on actual costs and work performed, it can produce performance forecasts for projects.

Organizations implementing an EVMS for the first time commonly lack a cost engine that can handle the needs of earned value management. If this is the case, make sure to choose a cost engine that integrates with other parts of the EVMS, as well as enterprise resource planning software, material requirements planning software, and estimating tools.

The Reporting Engine: This helps teams interpret and communicate EVM data. Although the cost engine already partially provides this function, a reporting engine allows for more in-depth EVM data reporting and the provision of EVM data analysis capabilities more widely across an organization.

The Accounting System: Most organizations already have an accounting or general ledger system in place, so it’s typical to integrate the existing system with the EVMS rather than install a new accounting system.

An EVMS can bring several benefits to the performing organization. Chief among these are the speed and accuracy of determining and communicating a project’s current status and performance. As long as the scheduling and cost engines and the accounting system are well integrated, an EVMS makes it easy to gain a snapshot of project performance - regardless of the size, duration, or complexity. For such projects, real-time visibility facilitates better decision making and enables timely corrective action. Further, consistent project tracking makes auditing performance data much more straightforward.

An EVMS also provides competitive advantages and ensures compliance. For example, having a specialized service provider install a properly integrated EVMS system is an easy way to ensure compliance with the 32 guidelines described by the EIA-748 standard (the standard for Department of Defense contracts). Further, properly implemented EVMS is likely to improve success rates with Requests for Proposals (RFPs) that require EVM implementation. This helps to explain why combined or all-in-one EVM tools, which provide scheduling, cost, and reporting functions in a single package, are gaining popularity.

Comparing and Selecting EVM Systems and Tools

There are quite a few options to consider when selecting EVMS components, and especially when choosing scheduling and cost engines. How do you decide which one works best for your organization? There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, so it’s important for organizations to carefully evaluate their specific needs before making a decision. Consultants and vendors can also help assess your EVMS needs and set up an integrated system to meet them.

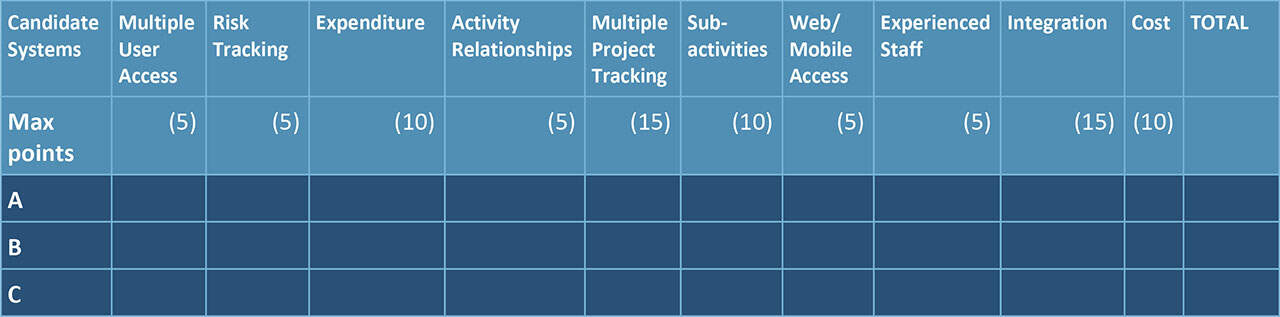

A good practice is to create a checklist of EVMS criteria that are important for your particular needs and conduct a decision matrix analysis. You can use a decision matrix to evaluate different options against the important criteria for your organization. You will find some of the most common criteria for EVMS and a sample decision matrix below.

First, an important qualifier: There is a debate in IT generally about whether organizations should choose the best components without regard to vendor or pick components from a single vendor (this debate is often framed as Best of Breed vs. Single Vendor). Proponents of single vendor argue that buying EVMS tools from one company will improve integration, while best of breed adherents say that there is no guarantee that components from the same vendor will integrate any better than those from different vendors. Considering that all desired criteria might not be available in a range of products designed by a single vendor, a best-of-breed approach may be a more practical solution.

How to Compare Earned Value Management System Components

What should you consider when comparing EVM system components? Here are some of the most important considerations:

- Risk Tracking: Does the scheduling engine allow you to record risks associated with project activities? Is the risk management capability built-in, or is it a separate feature?

- Expenditure: Can planned and actual expenditure be recorded at the activity level?

- Activity Relationships: How many types of relationships can you establish between discrete activities? Can you create relationships between activities from different projects?

- Multiple Project Tracking: Can you track more than one project at a time?

- Steps or Sub-activities: Does the scheduling engine allow you to create sub-activities that count towards the percent complete of the main activity?

- Web and Mobile Access: Does it offer web-based and mobile access for team members?

- System Familiarity and Ease of Use: Are the components in your solution widely used? For staff who are unfamiliar with any components, what is the learning curve and how easy is it to use?

- Integration: Do EVMS components integrate with each other and other systems you have in place, such as your database server?

- Sharing, Communicating, and Attachments: Is it easy for teams to update status within the system? Can you exchange messages? Does the system make it easy to attach and share things like photos, drawings, and plans? With EVMS, these features are often essential for documenting completion.

- Reporting: Your system needs to provide EVM analysis and reports. You’ll also want to assess whether there’s an easy way to glimpse key performance indicators, such as a project dashboard, and what functionality it has for alerts and status indicators to help flag problems.

- Foreign Currencies: Will you need to perform foreign currency calculations? Not all cost engines can support multiple currencies.

- EIA-748 EVM Requirements: If you need to meet EIA-748 standard requirements, make sure your components comply.

- Scalability: Will you want to manage multiple programs now or in the future? Do you have staff at multiple sites?

- Cost: How expensive is the scheduling engine? The hosted vs. cloud solution debate is common in all IT purchase decisions these days, and the consequences have implications for whether you will face greater upfront costs or an ongoing cost.

Here is a sample decision matrix that examines alternatives based on these criteria. Note that the criteria have different base scores because they are weighted according to importance.

If comparing choices A, B, and C, you’ll start by assigning each option points for each of the listed criteria. Work your way across row A and then down to rows B and C, totaling the points for each option when you’re done. The highest-scoring option of the three is the best pick.

Implementing Earned Value Management Systems

While a full implementation integrates all three aspects of project performance — scope, schedule, and cost — it’s not unusual for organizations to only examine a few components, such as schedule performance with earned value management.

Think of a task that’s completely automated and repetitive, such as the machine assembly of a complicated model car. Since the task is performed by a machine with a known efficiency and cost overruns are highly unlikely, actual costs are not as important as simply tracking the progress of work done on each car.

Varying levels of EVM implementation can be broadly classified as simple, intermediate, and advanced implementations. Determining the appropriate implementation is usually a function of the project’s total value, its goals and specifications, and the skill of the project manager and project team.

- Simple Implementation does not prepare a performance measurement baseline or consider actual costs. Instead, it simply tracks the project’s earned value without regard to a baseline. Such implementations are suitable for repeatable projects like the construction of our model car, where cost variance is low and where the main consideration is comparing the rate at which value is earned.

- Intermediate Implementation will assess performance using a baseline. This type of assessment is used for projects where the total project duration and the time to completion are important. As such, an intermediate implementation uses schedule network analyses to determine the expected duration of a project and will use that as a basis to gauge performance. Analyzing schedule variance is the main concern here.

- Advanced Implementation uses all the three metrics we’ve discussed — planned value, earned value, and actual cost — to track and analyze both schedule and cost performance. The term “advanced” might be a bit of a misnomer here, since it’s simply a full implementation of the concepts of earned value management.

The Limitations of Earned Value Management

Of course, project managers must keep in mind that traditional earned value management may not be suited to certain types of projects at all. For one, projects that do not have a clearly defined scope, such as discovery-driven or research-based projects, cannot be used with traditional EVM methodologies since it’s difficult to assign value to work packages without knowing just how many work packages there are and what they constitute. Additionally, projects where effort cannot be associated with discrete work packages aren’t suited to EVM methodologies because it is difficult to implement earning rules with sustained effort levels and no completion dates. (Level of effort is a term used to quantify work in earned value management when the work is not easy to quantify, such as knowledge work or services.)

Another area that can cause confusion is the use of planning packages in EVM. Planning packages act as a placeholder for groups of work that have not been defined in detail. As the work gets closer, these details become more defined. This is an EVM approach known as Rolling Wave that is commonly used with multi-year projects that are likely to face changes. Since it works with more distant horizons and larger groups of work, cost and schedule variance are more likely to occur with planning packages.

Another limitation is that, of course, EVM metrics are only as good as the data used to produce them. The whole point of using EVM is to set up an early warning system that catches potentially harmful variances from schedule and budget and corrects them quickly. If the system is working with outdated data, however, it’s not really providing up-to-date performance reports and its usefulness is severely limited. Non-software-based EVM may be prone to data problems for a number of reasons, but usually it’s because the accounting data used to compile actual costs is out of date. A properly integrated software-based EVMS goes a long way towards solving such data problems, since it guarantees timeliness and accuracy.

How to Make Sure Your EVM System is Performing

So how does a performing organization know that an EVMS really is doing what it is supposed to do? The Department of Energy manages this by conducting EVMS system project analysis, compliance reviews, and system surveillance.

System compliance reviews are conducted to ensure that a contractor’s EVMS complies with EIA-748. Depending on the Total Project Cost (TPC), DOE contractors may self-certify system compliance, or they may have to be certified by the DOE Program Management Support Offices or the Office of Project Management Oversight and Assessment.

System surveillance is carried out to ensure that a contractor’s EVMS reporting is both accurate and timely. The DOE also ascertains whether the contractor is using EVM data to drive decision making, and whether compliance to EIA-748 is being maintained.

How to Calculate EVM Metrics

We’ve already touched upon the basic metrics of earned value management: planned value, earned value, and actual cost. Here, we’ll delve into how to calculate and interpret these metrics. The Defense Acquisition University’s Earned Value Management “Gold Card” is a useful one-sheet reference for how to compute most EVM metrics.

Download Earned Value Management Gold Card

Budget At Completion (BAC): The total expenditure that will go into completing a project (the planned value when the project is 100 percent complete).

Planned Value (PV), or the Budgeted Cost of Work Scheduled (BCWS): The planned value is the budget allocated to project work that is due to be completed by a certain date. It is the baseline that earned value is compared to in order to determine any variance between the amount of work expected and the amount of work actually completed.

Calculate planned value at any point in a project using the formula:

Planned value (PV) = percent of work scheduled for completion (percent planned) X budget at completion (BAC)

or simply

PV = percent planned X BAC

The percent planned is simply the percentage of total project work that was scheduled to have been completed by a certain date.

Earned Value (EV), or the Budgeted Cost of Work Performed (BCWP): The budget allocated to project work actually completed by a certain date, as opposed to the work expected to have been completed by that date. Comparing planned value to earned value allows you to assess whether the project is running on schedule.

Calculate earned value at any point in a project using the formula:

Earned value (EV) = percent of work actually completed (percent complete) X budget at completion (BAC)

or simply

EV = percent complete X BAC

The percent complete is simply the percentage of total project work actually completed by a certain date.

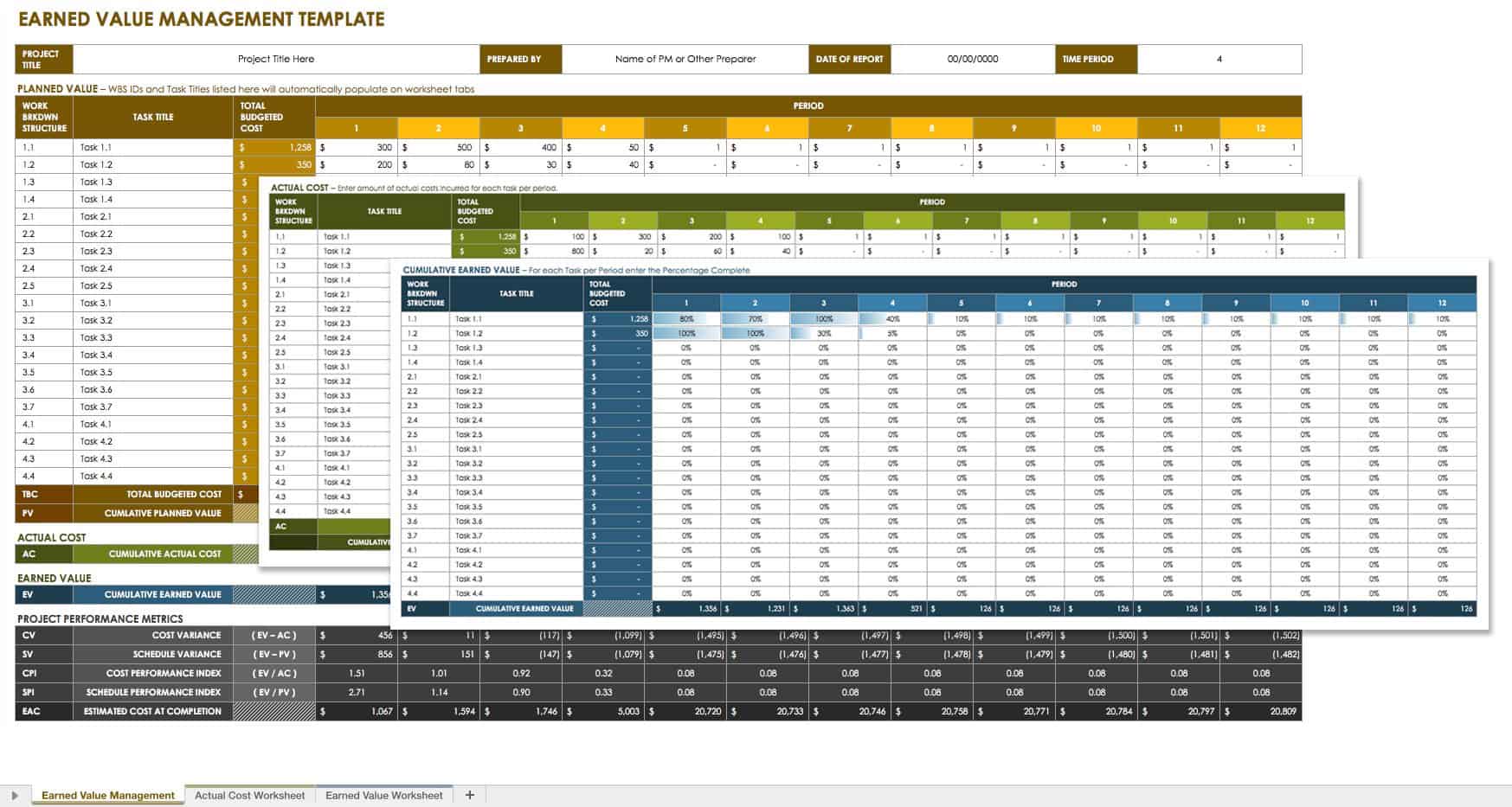

Download Earned Value Management Template - Excel

Actual Cost (AC), or the Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP): The total amount of money spent by a certain point in a project. The amount is compared to the earned value in order to contrast the budgeted cost of completing the work with the actual cost of completing the work.

Estimate At Completion (EAC): A forecast of how much money will be needed to complete a project once execution is underway. The EAC is calculated using another value: the estimate to complete (ETC). The ETC is the expected total cost of completing whatever remains of the project work.

It can be tricky to anticipate future costs and calculate ETC. It is most straightforward when the actual expenditure for work remaining is expected to tally with the budgeted cost of that work. In this case, calculate ETC using the formula:

ETC = BAC – EV

However, based on past spending patterns, the project manager might decide to adjust the ETC up or down.

The EAC is the sum of the actual cost and the ETC.

EAC = AC + ETC

The difference between the BAC and the EAC is called the variance at completion (VAC).

Key Concepts in Earned Value Management

The metrics discussed above form the basis of the key concepts of earned value management:

Cost Variance: Cost variance is the difference between earned value and actual cost — that is, the difference between the budgeted value of work completed and the actual cost of completing that work. It’s calculated using the formula:

Cost variance (CV) = EV – AC

If the cost variance is positive, the project is running under budget — this is called an underrun. If the cost variance is negative, the project is going over budget, called an overrun.

A useful summary statistic is the cost performance index (CPI), which is the ratio of earned value to actual cost.

Cost performance index (CPI) = EV/AC

A CPI greater than 1.0 indicates an underrun; a CPI less than 1.0 indicates an overrun.

Schedule Variance: Schedule variance is the difference between planned value and earned value — that is, the difference between the value of work expected to have been completed by a certain date and the value of work actually completed by that date. It’s calculated using the formula:

Schedule variance (SV) = EV – PV

A positive schedule variance means that a project is running ahead of schedule; a negative schedule variance means that a project is running behind schedule.

Another useful summary statistic is the schedule performance index (SPI), which is the ratio of earned value to planned value.

Schedule performance index (SPI) = EV/PV

An SPI greater than 1.0 indicates that a project is ahead of schedule; an SPI below 1.0 indicates that a project is behind schedule.

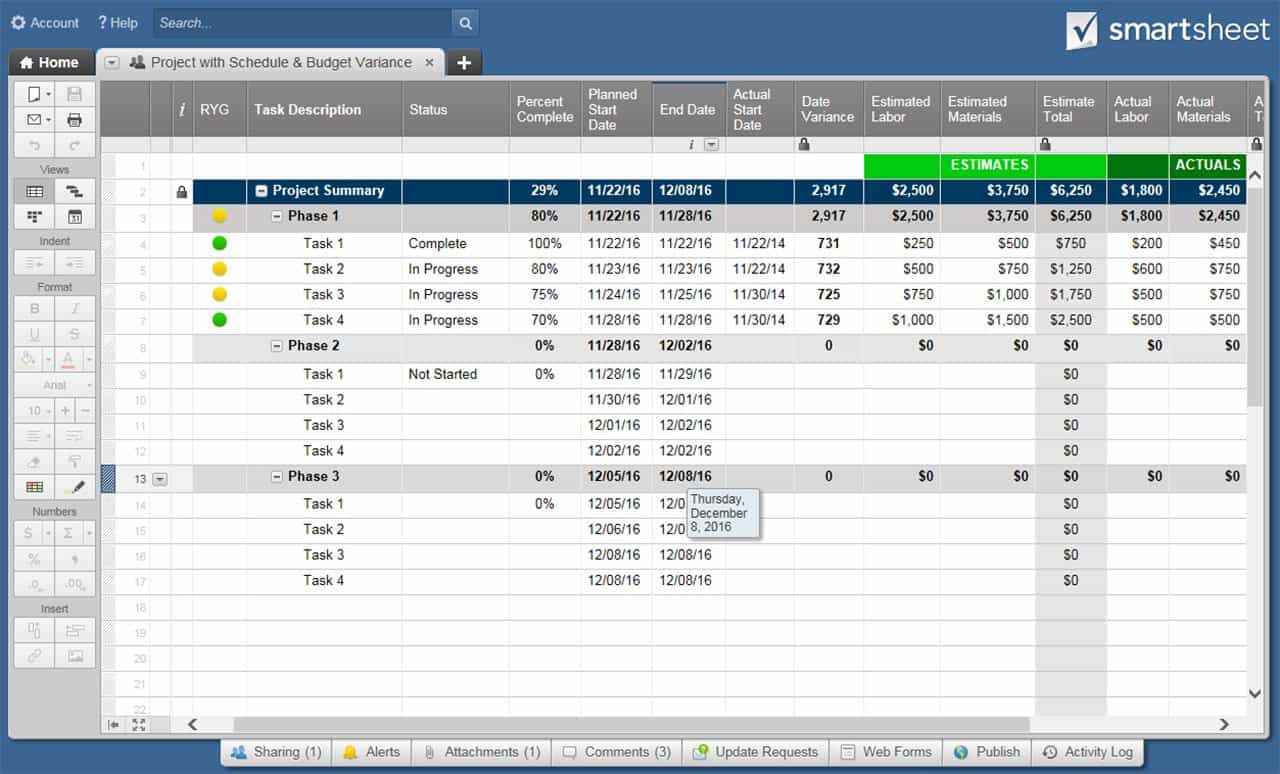

Use Project with Schedule and Budget Variance Smartsheet Template

Earned Schedule and the Problem with the Traditional SPI

The SPI is something of a flawed statistic. The Project Management Institute’s Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) describes the SPI as “a measure of schedule efficiency on a project,” but the traditionally-computed metric is nearly useless by the end of a project. At completion, earned value equals planned value, and so the SPI will be equal to 1.0 — even if the project was actually completed several weeks behind schedule.

The concept of earned schedule offers a solution: an addition to traditional EVM where the time work is completed is also taken into account. The formula does this by calculating schedule variance in units of time, rather than monetary units. For a deep explanation of earned schedule concepts, check out this conference paper, presented at the 2011 PMI Global Congress. In short, the two main concepts are:.

- Earned schedule (ES): The time at which a certain percent complete was expected to be achieved.

- Actual time (AT): The time at which said percent complete was actually reached.

Using the concept of earned schedule, you can calculate schedule variance using the formula below. Note the symbol used to denote schedule variance here is different from that used to denote schedule variance computed by traditional earned value management: SVt, not SV.

SVt = ES – AT

The schedule performance index (again, denoted differently as SPIt) is calculated using the formula:

SPIt = ES/AT

The concept of earned schedule also allows you to forecast the time needed to complete a project, which traditional earned value management does not allow. Use the formula:

Time estimated at completion = AT + planned duration of work remaining (PDWR)

Like the ETC, the PDWR is difficult to calculate. Depending on whether the project is expected to be completed at the planned pace or not, the project manager may choose either to simply subtract the time elapsed from the total amount of time planned for the project, or to adjust this figure based on past performance.

Standards for Earned Value Management

The EIA-748 Standard for Earned Value Management Systems is a set of 32 guidelines for EVM on Department of Defense projects and is the authority reference on earned value management. DoD contracts worth at least $20 million must comply with these EVM requirements unless waived by the Milestone Decision Authority. EVMS can be assessed based on their compliance with these guidelines, and service providers will offer to set up integrated EVMS to meet each of the five sets of guideline requirements detailed below.

- Organization: This first set of five guidelines deals with setting out the scope of the work via a work breakdown structure and a program organizational structure to determine how and by whom work will be authorized and performed. The planning, scheduling, budgeting, work authorization, and cost accumulation functions are also to be fully integrated with each other and with both the work breakdown structure and the program organizational structure.

- Planning, Scheduling, and Budgeting: These 10 guidelines center on the creation of a project baseline and the determination of total planned value using schedule network analysis, the program budget, and the complete scope of the work as detailed in the work breakdown structure. Specific guidelines also deal with best practices regarding the use of control accounts, the creation of management reserves, and how to deal with budgeted values for level of effort activities.

- Accounting Considerations: This set of six guidelines simply deals with how to record and summarize costs as part of earned value management calculations.

- Analysis and Management Reports: This set of six guidelines details best practices for earned value analyses. One of the more important requirements is establishing a calendar by which cost and schedule variances are examined and reported to management. How to report variances is also addressed, as is the need to continuously revise EACs throughout project execution.

- Revisions and Data Maintenance: Scope control is integral to effective earned value management, so this last set of five guidelines outlines how to manage changes to the project baseline. Most notably, changes in scope should be reflected by changes in project duration and total budgeted costs.

Oversight of EVM practices throughout the Department of Defense, in accordance with EIA-748, is carried out by the Office of Performance Assessment and Root Cause Analyses.

Use Smartsheet Dashboards to Provide Greater Visibility Into Earned Value

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.