What Is a Lean Management System?

The term lean is used a lot these days, but many people are not clear on what exactly it means. Lean management is a long-term approach to running an organization that seeks to continuously maximize customer value and minimize waste. Lean managers view waste as time, labor, or financial costs that do not add value for the customer.

Lean management systems are a long-term approach because waste is usually not eliminated in one stroke, but rather is trimmed away by repeatedly — this makes processes a little bit more cost-, labor-, or time-efficient. As such, lean management principles aim to achieve incremental improvements. Rather than being a top-down approach, lean management draws much of its effectiveness from a systematic way of thinking that is cultivated at all levels in an organization. Lean organizations trust the wisdom of people who are close to the processes and therefore able to spot and eliminate waste.

Lean management is usually traced to Toyota founder Kiichiro Toyoda, who in the 1930s created kaizen improvement teams to address problems with the company’s engine casting process. (Kaizen is a Japanese term that refers to business programs of continuous improvement.) His lean ideas became formalized in the Toyota Production System. The philosophy of lean, however, precedes Toyota, and it dates at least as far back as Benjamin Franklin, who warned against time-wasting and advocated incremental saving in Poor Richard’s Almanack.

Franklin’s advice influenced the leading figures of early American scientific management who applied scientific methodologies to the management of labor. Efficiency expert Frank Gilbreth, for example, sped up the work of masons twofold by creating a scaffold that placed bricks at waist level, so they didn’t have to stoop and pick each brick off the floor. Mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor advocated the lean philosophy of adoption at all levels in Principles of Scientific Management in which he recommends that process improvements suggested by workmen should be tested and adopted if they yield increased efficiency. Automobile pioneer Henry Ford was among the famous early practitioners of lean manufacturing in America. He had a remarkable ability to spot waste — not just in manufacturing processes, but in other productive endeavors too, as he observed in his 1922 book My Life and Work.

The need for waste reduction preoccupied American manufacturers through most of the 20th century as they recognized the threat posed by overseas manufacturers who benefited from cheaper labor. The solution suggested in the 1920s by Henry Towne of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in his foreword to Frederick Winslow Taylor’s Shop Management was for American manufacturers to aim for ever-increasing efficiency in their manufacturing processes.

The formal introduction of lean management principles to the United States, however, only came in 1988, when a former Toyota quality engineer named John Krafcik published “Triumph of the Lean Production System,” an article based on his master’s thesis at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Scholars at MIT’s International Motor Vehicle Program continued his work on “lean production,” and in 1990 released The Machine that Changed the World, a book by James P. Womack, Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel Roos. The book became an international bestseller and would play a vital role in popularizing lean manufacturing in the United States.

The term lean can cause confusion because it carries a lot of different meanings that each capture a different lean paradigm. Conventionally, lean refers to management as a process without end in which there’s always waste to eliminate and greater efficiency to achieve. Therefore, it can be said that an organization that practices this approach is always becoming lean. At other times, however, managers treat lean as a fixed, measurable, and achievable state of efficiency, so the emphasis is on achieving and maintaining specific efficiency benchmarks. This paradigm is known as being lean.

Alternatively, lean may refer to the tools associated with lean management techniques, and the emphasis here is on adopting proven efficiency-enhancing methodologies across many organizational areas besides manufacturing. Some may refer to this method as doing lean, which managers adopt to achieve quick efficiency gains. However, the method doesn’t employ lean thinking in the organization’s own unique work processes. (That explains why consultants like McKinsey dismissed this paradigm as not unlocking the full potential of lean.)

Lastly, there’s thinking lean, which is lean as a philosophy that targets waste for elimination whenever and wherever it is evident. Lean thinking is all-encompassing: It’s practiced throughout a company, and it shifts management’s focus from individual components to a cross-organization process by which value is created for customers, regardless of whether the business provides a product or a service.

Project Management Guide

Your one-stop shop for everything project management

Ready to get more out of your project management efforts? Visit our comprehensive project management guide for tips, best practices, and free resources to manage your work more effectively.

The Central Elements of Lean Management Principles

A lean management system defines value from the customer’s perspective and seeks to identify each step in the business process that produces that value for the customer, whether the end product is a good or service. The goal is to make the value-creating steps occur in a tight sequence with no waste. Kaizen, or the continuous improvement process, offers the means to achieve this efficiency.

Lean managers map the complete process by which value is created and delivered with value stream mapping, a visual diagramming process that shows how a product goes from raw materials to a package on a doorstep, identifying each step along the way. Management will pore over a value stream map, looking for steps that don’t add value and targeting them for elimination. For example, time spent in inventory does not add value for the customer, so shortening or eliminating it reduces waste. The same process works for knowledge products, such as software, or services (such as legal representation). The hypothetical end goal is a perfect value stream with zero waste that delivers perfect value to customers.

Lean cannot truly be achieved with top-down implementation as a set of directives from management. Instead, lean must be cultivated universally as a way of thinking that starts with the workers who are closest to a process and therefore know the most about it. Lean thinking must be fluid and open; it cannot thrive if it limits what workers can do or say about their day-to-day processes.

Japanese industrial engineer and legendary manufacturing expert Shigeo Shingo, a proponent of the Toyota Production System, understood this concept well. He did not direct frontline workers on how to increase efficiency, but instead challenged them to make recommendations as a team. By observing the current state, designing efficiency improvements, testing these, and then implementing the most efficient solutions, frontline workers were critical to Toyota’s lean endeavors.

Lean management methods deliver many benefits. Lean processes require less labor input, take up less physical space, consume less capital, and take less time to complete. This makes information management for processes simpler and typically more accurate. The products and services cost less and contain fewer defects. Simpler processes enable organizations to respond to evolving customer desires with flexibility, variability, quality, and quick turnaround. Lean leads to happier customers, increased productivity, and greater profitability.

Lean Manufacturing and the Toyota Production System

Since lean management arose in manufacturing, lean is closely identified with the production of tangible goods. Lean manufacturing sometimes goes by the name lean production or simply as lean.

In manufacturing, lean management is typically a systematic method of minimizing waste (with one significant exception, the Toyota Way, which we’ll cover shortly). Many consider lean to be synonymous with the Toyota Production System (TPS) and it owes much of its popularity to Toyota’s longstanding success as a manufacturer. But there are significant differences between TPS and plain old lean manufacturing.

TPS came together at Toyota as a function of several manufacturing methodologies and historical phenomena, and it is considered the brainchild of Japanese industrial engineer and businessman Taiichi Ohno, who himself moved up the ranks from the shop floor at Toyota to an executive position. Historically, TPS may have evolved out of necessity in Japanese postwar economy, which helps explain why pull production (the practice of manufacturing to order rather than to target) was a central tenet.

But Ohno also pulled together a number of related practices in Japanese manufacturing, such as visual control known as Kanban, the kaizen process of continuous improvement, and autonomation or jidoka. This last term, classically defined as “automation with a human touch,” originated in Sakichi Toyoda’s textile factories, and is a paradigm of manufacturing where machines check their output for conformity with manufacturing standards. They stop if nonconformity is detected, and a human steps in to take stock of the problem. The person then designs and implements a solution, and restarts the process.

Autonomation is one of the TPS’s two pillar concepts; the other is just-in-time production (JIT). This method is a pull-production process in which materials are delivered immediately before they are needed rather than being stored. The goal is to reduce inventory and storage costs. Indeed, the TPS was initially referred to as just-in-time production until the 1990s when the term “lean” gained popularity.

Like conventional lean manufacturing, TPS defines value from the perspective of customers as any action or process a customer is (or would be) willing to purchase. Anything that doesn’t add value is considered waste and is fair game for removal. Toyota defined three broad categories of waste known as the 3M: muda, muri, and mura.

Muda is processes or actions that consume resources but do not add customer value; muri is waste created by the overburdening of employees or equipment; and mura is waste, or wasted capacity, brought about by unevenness in production workloads. Lean manufacturing outside of TPS typically focuses only on reduction of the first waste, muda, and its seven constituent waste subcategories: transport, inventory, motion, waiting, overproduction, over processing, and defects. But muda may be a symptom of a production system’s mura and muri.

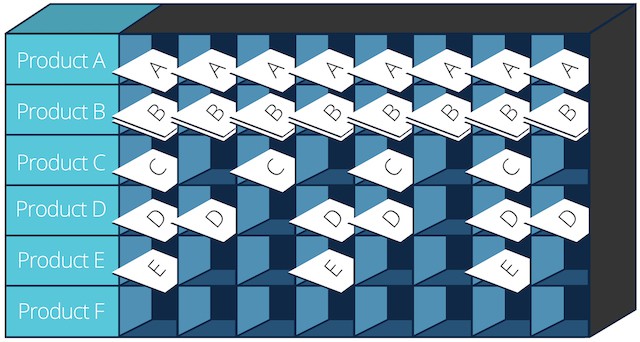

This is where lean manufacturing departs from the Toyota Way. TPS is not strictly waste (muda) reduction per se. Rather, it focuses on the smooth flow of production through such techniques as production leveling, pull production (such as by using Kanban), and the heijunka box, a visual scheduling tool. The heijunka box is typically a wall schedule that consists of rows of pigeon holes with each hole representing production shifts. Kanban cards representing individual jobs are placed in each shift slot to illustrate what will be produced in that production period.

Production leveling means producing intermediary products at a constant rate to prevent bottlenecking; pull production is the practice of creating intermediary products only when the next process downstream is ready for them. The resulting smooth flow of production quickly exposes quality problems that would otherwise lie hidden in inventoried items. The operation also reduces the mura and muri of a system, and thus decreases the amount of muda.

Both lean manufacturing and TPS aim to reduce costs by eliminating waste, and both benefit from the application of lean methods: designing simple manufacturing processes, recognizing that there is always room for improvement (whether as waste removal, production smoothing, or both), and then tailoring the production system to make these improvements.

There are differences. TPS is more profit-oriented, while lean management focuses on performance improvements first. TPS also emphasizes managerial training and puts responsibility for lean improvements on “natural” work teams led by skilled supervisors rather than on external change agents. Many organizations who attempt lean manufacturing do the opposite.

Lastly, there’s a tendency in some lean manufacturing implementations to view tools as problem-solvers. In TPS, tools and techniques primarily diagnose problems, not fix them. Even then, managers realize that no single tool can effectively address all the complex aspects of a production process.

The Lean Management Tool Box

Lean implementations will incorporate many tools to identify and eliminate waste. Here are some of the most frequently used.

SMED: The single-minute exchange of die (SMED) is a lean production principle that applies to processes where changeovers of any sort are necessitated between each production lot. (A die is a manufacturing tool used to cut or shape material and is customized for a particular product type.) According to the SMED, die changeover should take less than 10 minutes (i.e. a single-digit minute) every time. This principle smooths production and helps reduce production lot sizes.

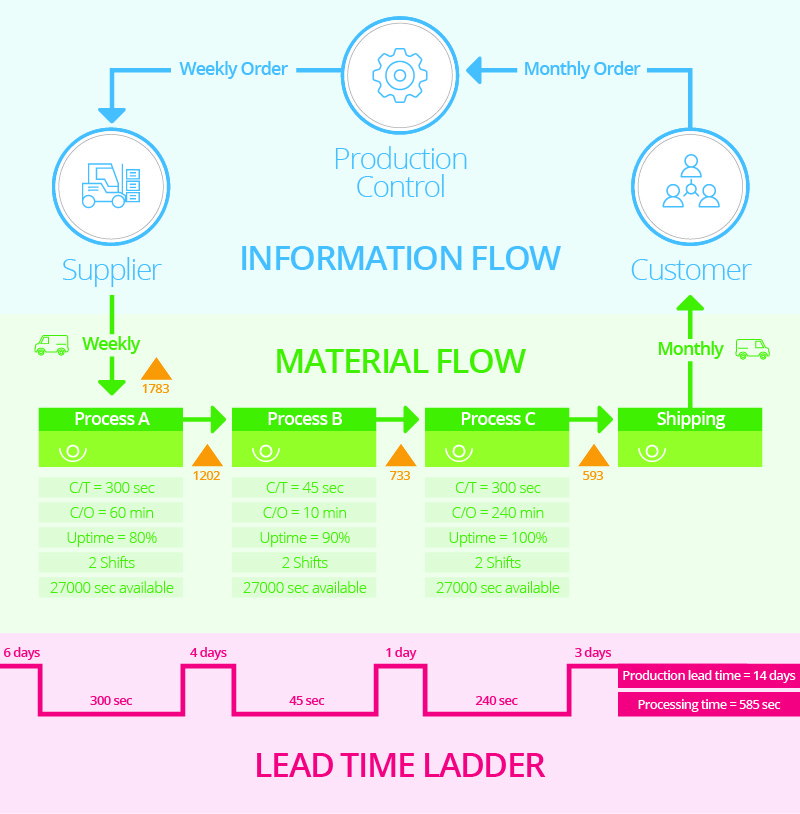

Value stream mapping: Value stream mapping is a lean method for depicting and analyzing the process by which value is created and delivered to a customer, from beginning to end. The value stream map looks something like a complex flowchart, with the core value-creating steps placed in sequence across the center of the map and non-value-creating steps detailed at right angles to the value-creating steps with which they’re associated. (Non-value-creating steps are typically preparatory or operations activities.)

An initial value stream map represents the current state of a production process at a particular point in time, and uses the current state map as the basis for a future state map with reduced waste steps. In manufacturing, the value stream map would be a flow chart of materials through the production process.

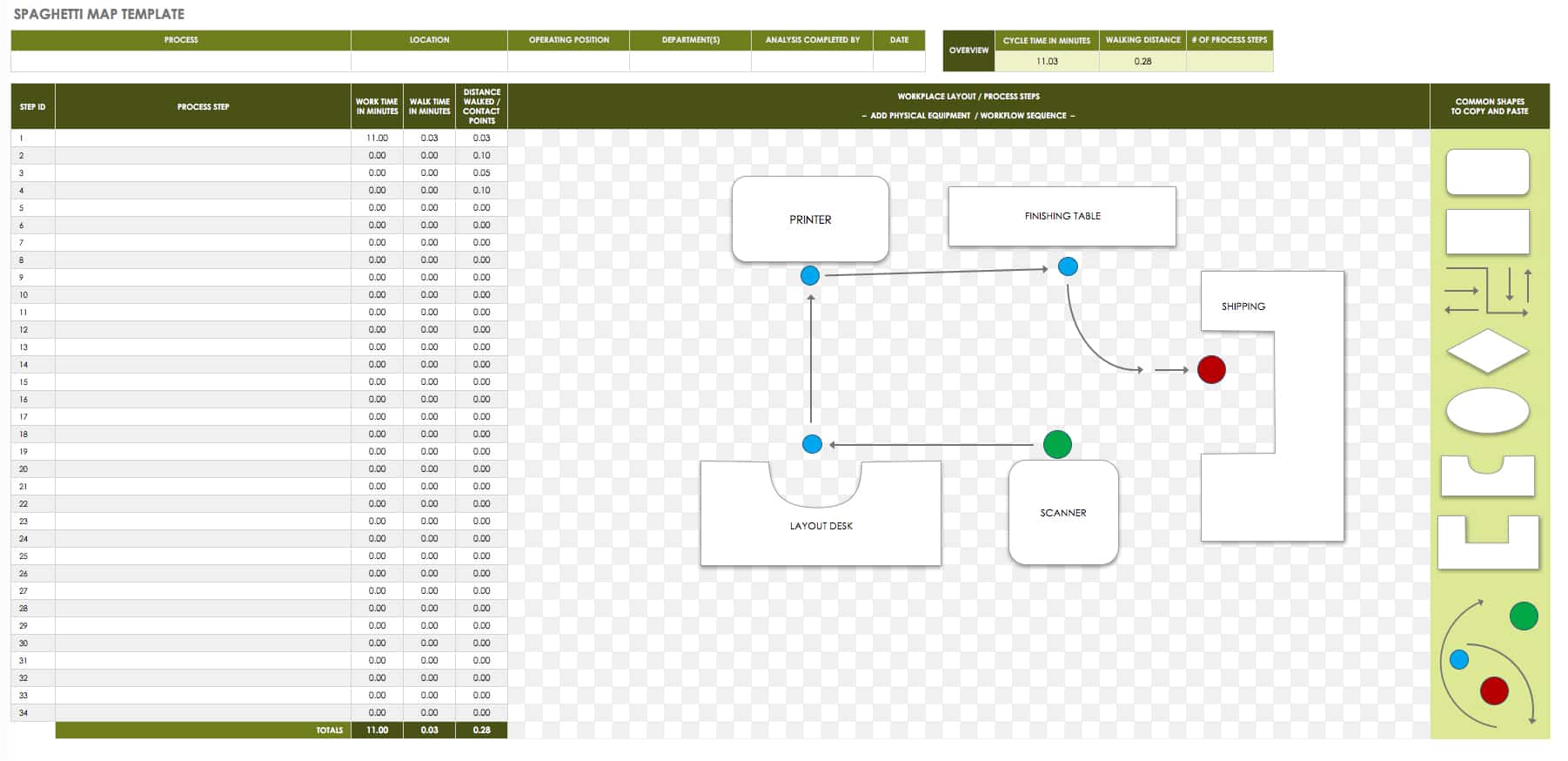

Mapping the value stream means using visualization techniques such as Kanban, flowcharts, or spaghetti diagrams to represent this flow. Toyota pioneered the technique of value stream mapping, which allows business managers and strategists to identify parts of the value stream where waste occurs, and optimize the value stream to reduce waste. A spaghetti diagram is a great starting point because it visually documents the actual flow of product, paper, and people in a workplace or project workflow. Use the below template for a spaghetti diagram below to make your own.

Download Spaghetti Map Template

Experts recommend creating a value stream map with pencil and paper and documenting all the process steps that your product goes through, from supplier to your organization and finally to the customer.

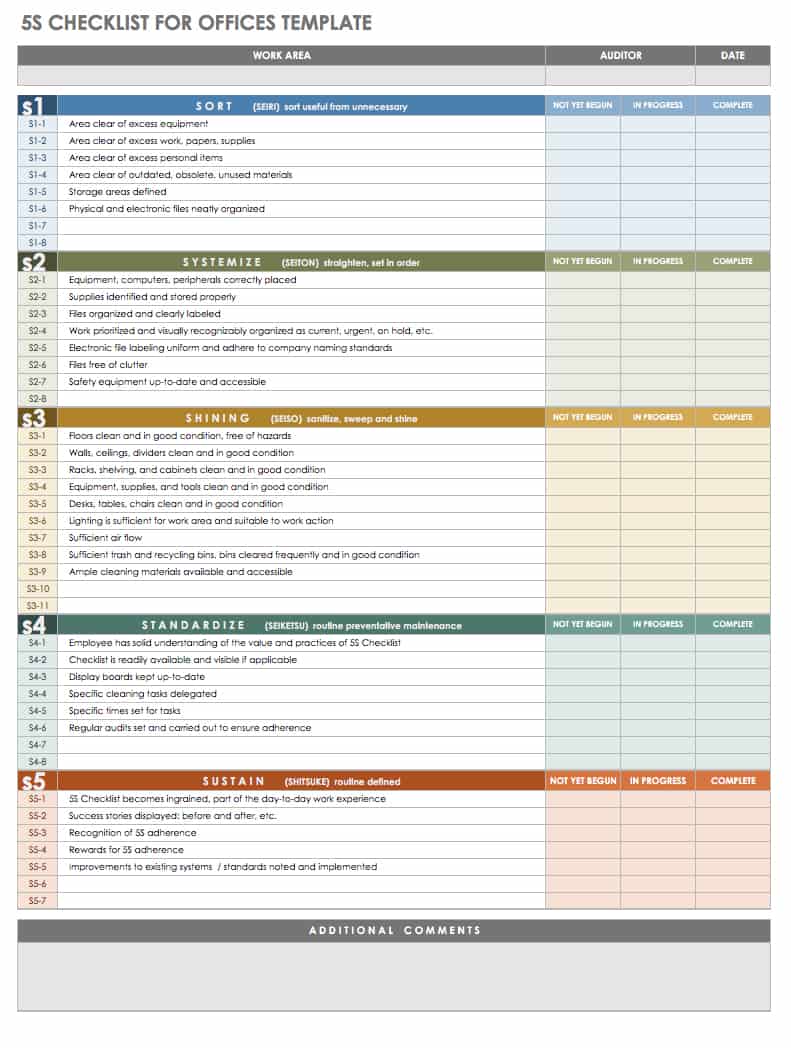

Five S: The 5S is a set of workspace organization principles designed to maximize physical workspace or work station efficiency. It stands for sorting, straightening, shining, standardizing, and sustaining. Sorting is identifying which tools are needed and getting rid of the rest; straightening is assigning an identifiable space for each tool; shining is maintaining workspace cleanliness; standardizing is establishing a set of rules or procedures for using the workspace; and sustaining is making sure the rules are followed consistently. These principles work in both production environments and offices. See the checklist below for offices.

Download 5S Checklist for Offices Template

Kanban: The Kanban system of visual scheduling and work management is based on a simple truth: People grasp pictures faster than they do words. A simple Kanban system consists of a large whiteboard split into sections. Each section represents a production sub-process in sequence. Colored Kanban cards that represent a specific work item or production lot are placed on the board. (These can be index cards, sticky notes, or digital cards.) As these items proceed sequentially through the production process; they move from one section of the board to the next.

Kanban shows at a glance exactly how many items are at a particular stage in production at any given moment, which makes it easy to control and smooth the production flow and to assign additional resources where necessary. Any defective items are not moved on to the next stage, so Kanban helps quality assurance. Kanban is popular in manufacturing but also software development and other service industries.

Poka-yoke: A poka-yoke is a mechanism designed to help human operators catch and correct intermediary product defects before they move down the production chain. A poka-yoke device thus provides low-level error proofing. The poka-yoke helps minimize waste by preventing defective products from moving onto the next stage of production, where they’re likely to incur wasted labor and transport costs — not to mention causing frustration to workers downstream. An example was a system that Shigeo Shingo used in the 1960s to prevent workers from forgetting to install two springs in a switch assembly. He redesigned the process so that if they saw they had a spring left after assembling a switch, they knew they had forgotten to install one.

Total productive maintenance: Total productive maintenance (TPM) is a system for maintaining the equipment and employees that create value for an organization. It’s meant to keep things in prime working condition to minimize breakdowns and delays.

Eliminating time batching: Time batching is the practice of processing intermediary products a batch at a time, thus waiting until a certain number of items are ready before the process can begin. Batching creates inventory costs, reduces production smoothness, and can hide defects from previous steps until they drive costs up significantly.

Mixed model processing: Mixed model processing is the use of a single production line to work on different product models a few units at a time, rather than processing large batches of one model before changing over to another. It is meant to prevent the accumulation of inventory and smooth downstream production processes. However, mixed model processing is only possible when working with small batches and when you can affect quick changeover times in between models.

Single point scheduling: Single point scheduling is an attempt to reduce the complication of scheduling at several different points within a value stream. It uses a single signaling tool known as a pacemaker to request production from upstream processes. Single point scheduling gets its name from the single point that generates a pull signal — the so-called pacemaker. Processes downstream of the pacemaker are managed to maintain a continuous flow.

Control charts: A control chart is a quality control tool that tracks process output in graph form. It’s used to make sure that process output stays within “control” — that is, it doesn’t stray beyond preset acceptable quality limits. If this happens, it’s an indication to examine the process to identify the sources of output variance.

Multi-process handling: Multi-process handling is the practice of training operators to work a number of sequential steps in a production chain, so they can “walk” intermediary products through operations. This practice is different from the usual production setup, where each operator only works on a single production step.

Rank order clustering: Rank order clustering is an algorithm used in designing manufacturing cells, an integral design element of JIT and lean manufacturing. A manufacturing cell is a unit comprising one or more machines that accomplish a certain task. They’re designed to minimize operator movement, thus reducing waste.

Six Sigma: This is a process improvement methodology with a simple goal: the near elimination of defects in the outcome of a process. Six Sigma is data driven, and the name is a statistical reference to having six standard deviations between the process mean and the nearest specification limit, which translates to an error rate of 3.4 defects per one million process outcomes. Six Sigma is similar to the kaizen process of continuous improvement, as it too subscribes to a philosophy of continuous improvement. The difference is that kaizen seeks to improve process efficiency, while Six Sigma aims to improve process outcomes.

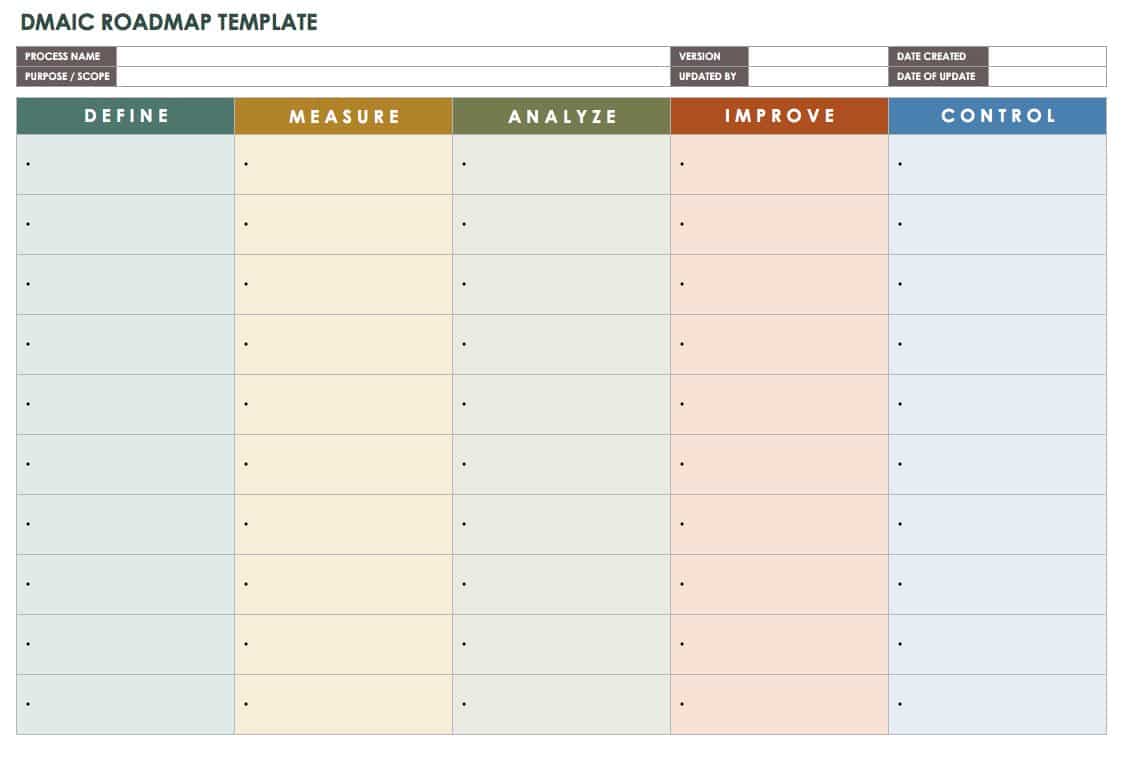

DMAIC is a Six Sigma improvement cycle for existing processes (he acronym stands for define, measure, analyze, improve, control). The define phase sets the scope of the problem to be examined and establishing customer value requirements. Measurement is the evaluation of the process’s current state using statistical data. Analysis is the process of examining this data to identify the root cause of the variance in product outcome. Improvement is the application of process-improvement techniques to optimize the process, transitioning it to a future state with more consistent quality outcomes. Control is monitoring the new process to ensure that quality of output is maintained. Repeat DMAIC until you reach a desired level of outcome consistency.

Download DMAIC Roadmap Template

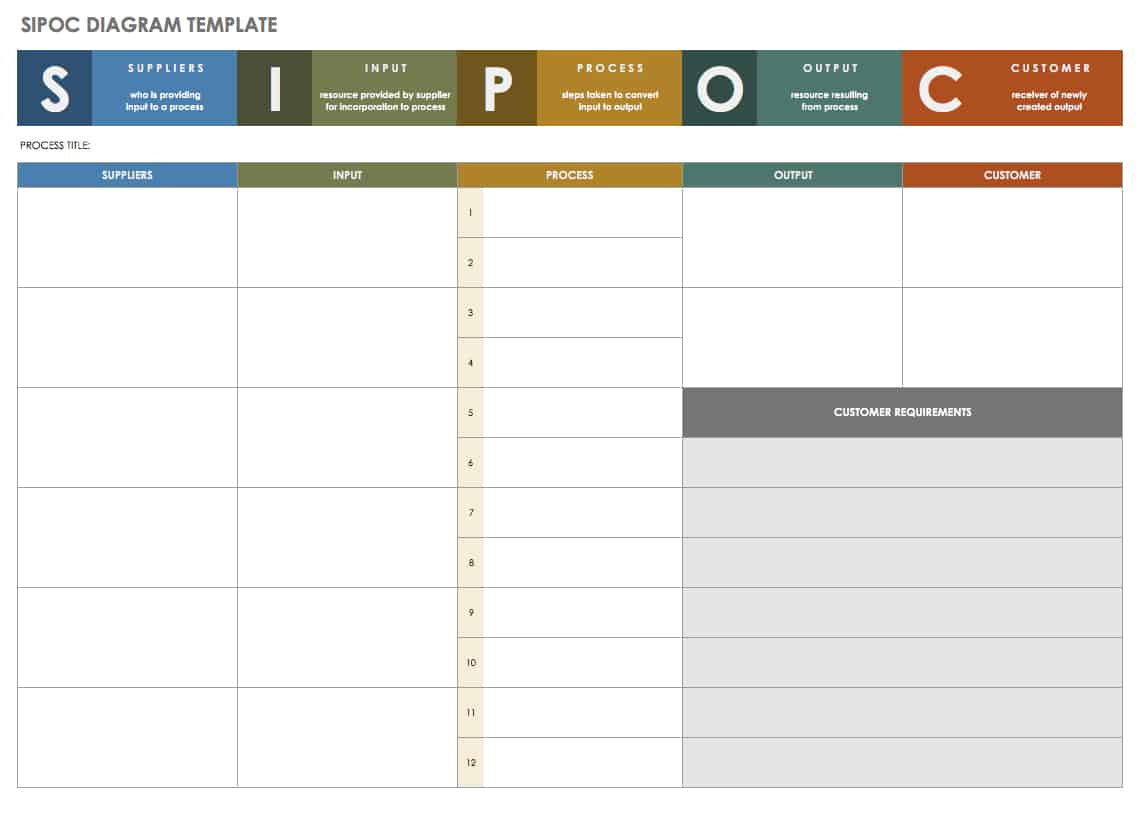

SIPOC: SIPOC stands for suppliers, inputs, process, outputs, and customers. A SIPOC diagram provides a high-level, visual overview of a business process, which is helpful for identifying and summarizing all of the elements in a process improvement project from start to finish.

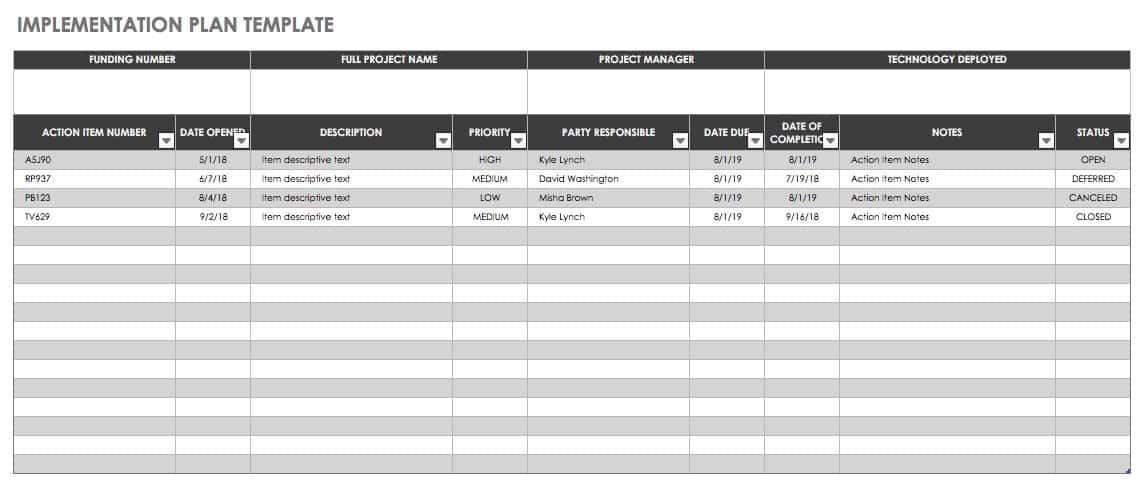

Download Implementation Plan Template

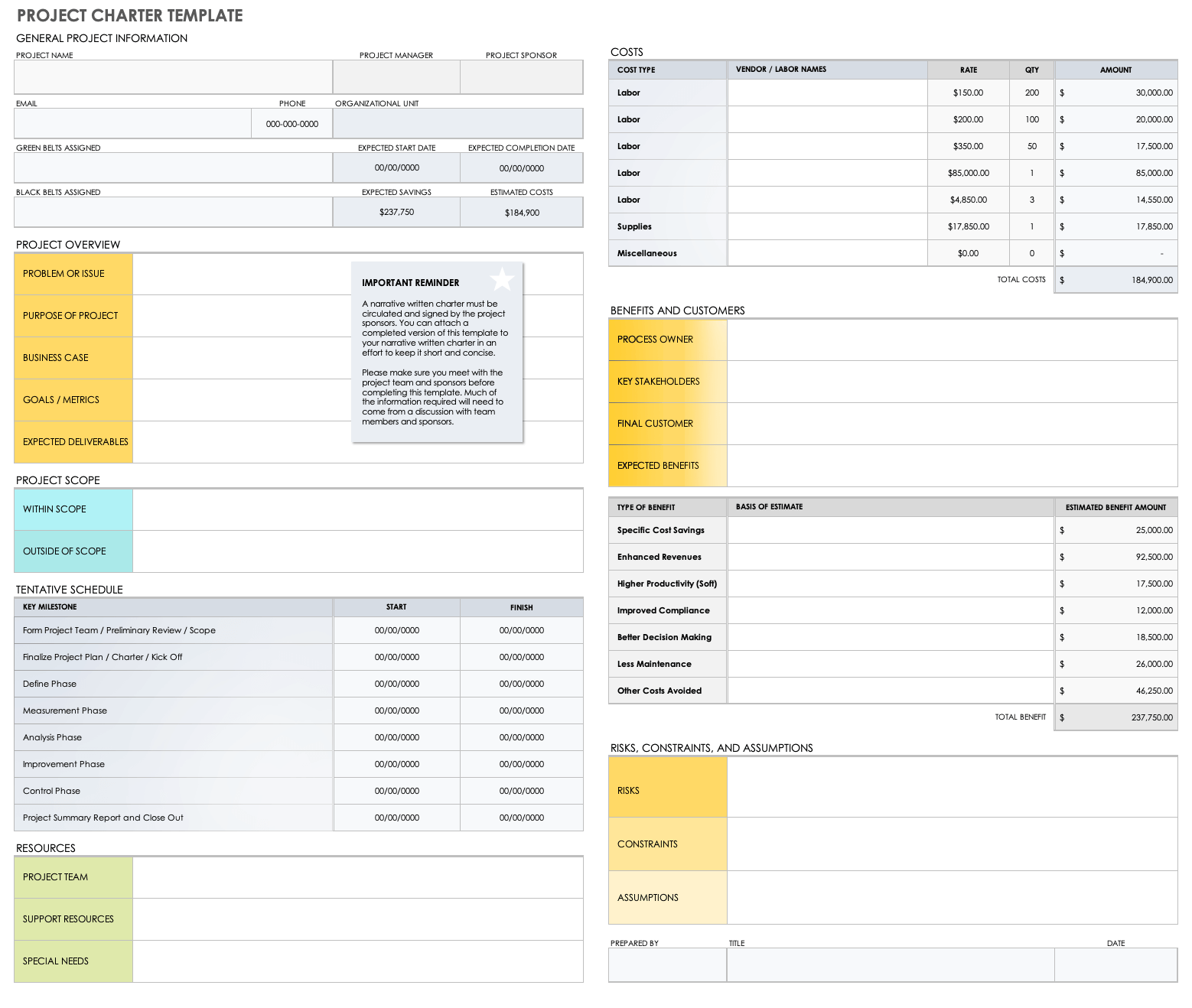

Download Project Charter Template

Excel | Word | Smartsheet

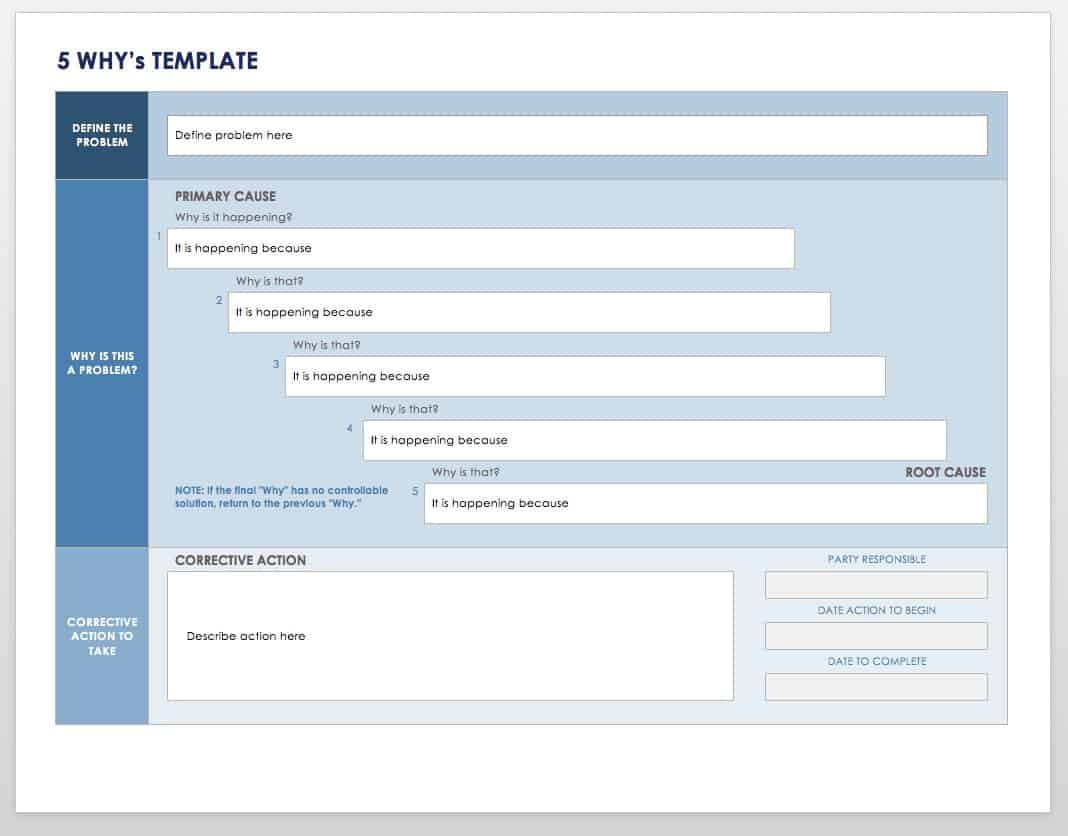

Five Whys: Five Whys is a simple yet powerful approach to drilling down and solving problems that works well with kaizen. You ask why a problem happened five times to identify the real root cause of a problem and address it. Like other lean tools, it works well with shop floor operators but is also suited to facilitating discussions with participants from different levels of the organizational hierarchy. Five Whys can also reveal workers’ and management’s preconceptions about production conditions.

Download 5 Whys Template

Excel | Word | Smartsheet

Critical Components of Lean Management Systems

A lean management system, according to Joe Murli, CEO of The Murli Group, has several elements. These enable an organization to maintain, sustain, and continue their lean improvements.

The first critical component is knowing your organization’s “true north,” or its vision of the ideal state. Your organization needs to define where it wants to go before it can get there. The vision is critical to organization-wide alignment with goals and to ensure executive buy-in into lean strategic planning and deployment. Your vision should emphasize the performance of the entire value stream, all the way down to the customer.

Next comes standardized work practices in the organization. The Lean Enterprise Academy defines several characteristics of unstandardized work, including the prevalence of variation that regularly impacts customers, employees, or finances; the use of multiple methods to accomplish the same task; and the lack of certainty over quality, delivery, safety, and cost. Unstandardized work is a huge source of waste, and it cripples efforts to improve efficiency. Standard processes will enable staff to implement lean improvements and reap benefits.

The third component is visual management such as Kanban. It’s faster and easier to understand and leaves little room for a misunderstanding. Of course, more efficient communication means less wasted time.

A focus on developing your people is another critical example. That means developing problem-solving and lean thinking muscle throughout an organization, not just in its leaders. Otherwise you’ll end up with individual firefighters, not collaborative problem-solving teams. This is called developing the people value stream, and it’s a process that HR should help enable, not be required to police as enforcers. By doing this, you’ll foster diverse perspectives on problem solving, since you’ll have problem solvers who understand problems firsthand. Make departments or work teams accountable for specific types of issues. In a truly lean organization, most employees are engaged with the lean approach. This doesn’t have to be complicated; it can be phrased as questions that encourage staff to think of improvement in simple terms. Ask teams to answer three questions: How did we do yesterday? Where was the waste? How can we do better today?

Ensure that company leaders model lean thinking behaviors and seek to develop these in teams, not quash them. Lean only works if improvements created at the frontline or on the shop floor are actually made possible.

Remember that lean improvements, once enacted, need to be maintained. Therefore, a strategy for sustainment is crucial. Lean endeavors do little good if organizations lapse back into wasteful ways of doing things. The drive for improvement should be consistent and perpetual, so a forward momentum holds. One way to build enthusiasm for this is to measure and record the impact of lean improvements on performance metrics.

For a deeper discussion of what goes into an effective lean management system, check out The Lean Management Systems Handbook by Rich Charron, H. James Harrington, Frank Voehl, and Hal Wiggin. Murli cites several organizations that have succeeded with lean management systems including General Electric, Moog Aircraft Group, and the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality.

Lean Management Improves Efficiency in Service Industries

There’s a common misconception that lean management is suited only to manufacturing. While lean originated in manufacturing, managers have embraced it in many service organizations and industries, including IT, call centers, construction, government, and healthcare. Lean managers in service industries have fewer historical examples and a much smaller body of literature to reference. As lean management spreads, those barriers become smaller.

Lean brings significant improvements to global supply chain management, cost savings, and better customer experience. Dell and Zara bear testament to the success of effective global supply chain management using lean principles.

Professor Gal Raz of the University of Virginia’s Darden School Foundation explains how Dell maintains close contact with its customers — in turn, this practice allows the company to more closely match supply with demand while reducing inventories. Zara’s fast-response supply chain allows the company to make design and production decisions within a fashion season, which in turn helped it achieve 20 percent annual growth from 2001 to 2006.

That said, there have been documented problems with “stretching” the lean supply chain method too far. The most infamous of these cases is the 2010 Toyota recall for faulty accelerator pedals, which was rooted in Toyota’s lean-inspired preference for single-source component suppliers that in turn enabled their JIT production strategy. This strategy worked in Japan, where Toyota built years of trust working with particular component suppliers, but global expansion meant extending the same trust to more suppliers.

Another prominent application of lean management outside manufacturing is in the healthcare industry. Lean in healthcare is a set of operating principles and techniques designed to reduce waste and improve “customer” value by reducing patient wait times. Although healthcare and manufacturing are quite different industries, some parallels do exist: In both cases, the processes of delivering value to the customer/patient are complex and multifaceted, and waste, whether of money and medical supplies or patient time and goodwill, reduces customer value.

The benefits of applying lean principles in healthcare are documented: increased productivity and an improved customer experience. This Institute for Healthcare Improvement white paper describes the success of lean management at the Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, Washington. By eliminating waste, Virginia Mason saved millions of dollars on a planned expansion that was no longer necessary once it was able to more efficiently manage their existing facilities. It also reduced the number of full-time equivalent workers despite a no-layoff policy by increasing productivity and reducing a need to replace retiring employees. The hospital was also able to slash setup and lead times as well as reduce floor space used and distances traveled.

Is Lean Still Relevant in the Digital Age?

Lean management systems also face criticisms — for example, that implementers focus too much on tools rather than culture or that lean “change agents” tend to be too distant from the shop floor. For lean to be effective, management has to understand how it works at a fundamental level. Remember, lean isn’t a collection of tools but a way of thinking, and waste reduction works best when companies empower those who work on the shop floor to suggest and implement waste-reducing procedures.

There are also concerns about whether lean management is relevant for the modern organization. After all, lean is at least 70 years old, and there are questions about how well it works in the digital age, when “waste” may be less tangible.

Yet experts say lean thinking is even more needed today. Through the lens of lean, waste can be easier to spot even in service industries. Management consultant Shawn Casemore argues that lean shines in helping companies ensure that new technology achieves efficiencies and integrate a multigenerational workforce. Lean systems’ emphasis on engaging “shop floor” workers in process improvement efforts resonates with millennials, who seek empowerment rather than management from the top down. The improved operational efficiency brought by lean management can be a competitive advantage, as Dell knows well. Lean’s emphasis on identifying what customers value in a product helps support efforts to focus on the voice of the customer and break down organizational silos.

Leaders in a lean enterprise face key responsibilities. They must do the following:

- Sustain continuous improvement

- Create practices to support this improvement

- Ensure that the practices themselves improve continuously

- Integrate new technologies and optimize them

- Advocate for quality and safety for customers and staff alike

- Respect the voice of the customer and the customer’s needs

- Empower the front-line worker who is the process expert

- Encourage colleagues and employees to think lean

- Create a culture of accountability, not fear or blame

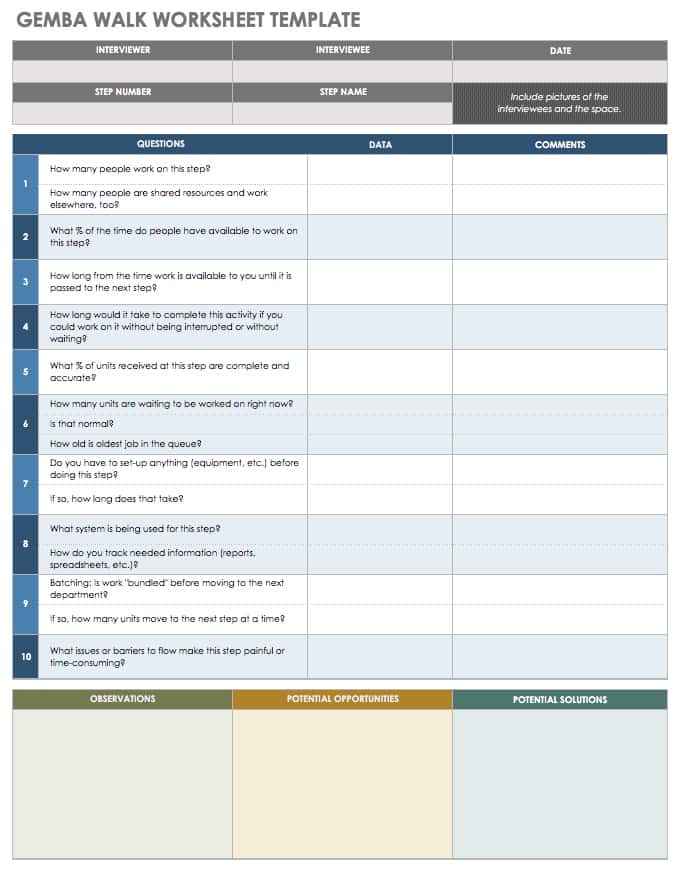

One best practice for lean leaders is the gemba walk (also known as the process walk in Six Sigma), which is an observation of the shop floor by a supervisor. The gemba walk comes from the idea that observing work as it occurs and where it occurs provides the most accurate source of information about work and thus is the most fruitful source of data for lean improvements.

The gemba walk isn’t about drilling fear into those who work on the shop floor or about telling them how they should do their jobs. Instead, it’s about observing quietly, with humility and respect, and holding open conversations with shop floor workers about what they think works and what doesn’t. Gemba walkers also use this as an opportunity to foster lean thinking skills in workers by encouraging them to identify wasteful practices and to form their own solutions to problems of waste, using techniques like the Socratic method.

Use this worksheet to take notes at each process step on your gemba walk.

Download Gemba Walk Worksheet

Is Your Organization Ready for a Lean Transformation?

If your organization is looking to go lean, first assess your readiness. Start by thinking about the three fundamental aspects of lean: purpose, process, and people. These are the keys to organizational transformation.

- Decide the purpose of your lean transformation. Lean can only be successful if it remains cognizant of customer value. What customer issues does the organization plan to solve?

- Select the process you will use to reassess your value streams. What will your organization do to mitigate waste and to ensure that processes flow smoothly and in pace with customer pull?

- Put your people in charge of your processes and your value streams. Does your organization have people who can make sure each value stream stays lean? Is everyone involved with a particular value stream encouraged to think lean? Check out “Creating a Lean Culture” by David Mann — a prize-winning book on lean transformations.

A Five-Stage Process for Implementing Lean Management Principles

If you’re thinking of implementing lean, the following five-step thought process can guide you through it.

- For each product family, specify the value from the customer’s perspective. Consider what users are looking to get from the product, and how much they’re willing to pay for it.

- Map the value stream for a product family. Identify each step in the value stream, and eliminate any that do not add value for the customer. Build consensus on this at all levels, from the shop floor to the C-suite. Give employees the autonomy they need to make decisions, and to evaluate them.

- Once you’re left with only value creating steps, set these up as a tight sequential process, so that the product flows smoothly toward the customer. Set up a one piece flow rather than batch processing. In this way, only a single piece of work moves between poka-yoke-proofed, 5S-compliant operations at a time. This minimizes work in progress and prevents defects from piling up. Calculate the takt time (how fast products must be manufactured to meet customer demand) and strive to make cycle times meet it through kaizen. Minimize changeover times.

- Let customer demand drive the production chain. Using a pull approach automatically keeps a control on inventory and work in progress, and it allows more responsiveness to customer demands and market changes. This type of efficiency will also help level out the workload.

- Reevaluate the production process repeatedly, until you come as close as possible to a zero-waste, perfect-value process. Keep track of performance metrics, so you know how — and if — you’re approaching your ideal state.

Remember, lean improvements are not limited to manufacturing industries. In fact, given the amount of variability in task performance in service industries, it’s arguable that standardization can cut more waste from service procedures than from manufacturing processes. One popular example from healthcare is hospital laboratory layouts, which require lab technicians to walk distances between pieces of equipment; over time, these add up. Standardizing the lab layout using 5S for common procedures can make it function remarkably faster.

Refining with Lean Daily Management and Lean Change Management

Companies can sustain lean implementations through the practice of lean daily management, which is a system of leader standard work, visual controls, and accountability and discipline. Leader standard work involves gemba walks, looking for anomalies, and supporting the kaizen improvement process.

Lean daily management simplifies the application of lean principles into these three elements: routines and expected behaviors for leaders, visual controls to facilitate ease of work operations and diminish the likelihood of errors/defects, and a system of accountability to keep processes on time and in sync.

Lean change management is a set of practices and ideas to help organizations navigate through today’s rapid pace of change. It incorporates Lean, Agile, Lean Startup, and brain research on how people adapt to change. Check out this interview with Jason Little, author of Lean Change Management: Innovative Practices for Managing Organizational Change to learn more.

Why Do Some Lean Implementations Fail?

Efforts to adopt lean management don’t always go right, and understanding why they fail can help you avoid that fate. Among the most ominous warning signs is a reliance on a single in-house lean champion, rather than on a community of lean thinkers. This setup renders a kaizen culture impossible and diminishes the potential for waste reduction. Also, improvements become limited and hard to sustain where they’re possible at all.

Sometimes, failure may boil down to a communications breakdown: Does everyone actually understand the concept of lean, and is there openness to experimentation and improvement? Other times, the benefits from lean implementations aren’t evident because before/after metrics weren’t comparable. Or, there may not be a genuine buy-in to lean principles from top management, which means almost everyone below them isn’t going to feel empowered to think and act lean.

Another pitfall occurs when the champions of the lean approach fail to develop a strong business case for adopting it. The nature of operations and staff at an organization might also make or break a lean transformation. For one, lean requires somewhat standardized, predictable processes to assess — otherwise, it’s a virtual non-starter. Also, lean thinking might not catch on because of a general reluctance to change workflows or due to more practical concerns like difficulties in getting employees up to speed with lean tools — especially digital ones.

Implementing lean in service industries can be particularly tricky, given the relative difficulty of applying concepts like pull and flow. Service processes are also much harder to parse and measure and typically much less standardized than manufacturing processes.

The term “lean management system” also describes software solutions that can help allay some of these difficulties. These tools provide a centralized platform for improvement projects, as well as maintain a standardized workflow. They help automate work processes, ease collaboration, and facilitate reporting, analytics, data visualization, dashboards, impact measurement, and broadcasting successes. Applications that enable automated actions improve productivity, reduce bottlenecks, and eliminate repetitive busy work. This means less wasted time and effort, which frees up staff to focus on the true priorities of lean transformation.

Enhancing Lean Management with Certifications and Qualifications

Learning more about lean is a great way to improve your success. There is much debate about which lean qualifications are most recognized, most beneficial, and the easiest or most difficult to obtain. Certifications differ widely in what they represent about the qualified person’s knowledge of lean methods. Some will only require taking a course while others will call for tests or evidence of practice experience with lean knowledge.

If you’re considering lean certification, do your homework and find out which qualifications your company or industry accepts and which are appropriate for your specific career focus.

The Lean Certification Alliance — which comprises the Association for Manufacturing Excellence (AME), Shingo Institute, and SME — offers three levels of lean certification (Bronze, Silver, and Gold) and requires both an examination and an accomplishment record or portfolio.

The American Society for Quality (ASQ) offers a variety of lean training courses. The ASQ, the International Association for Six Sigma Certification, and the Northwest Center for Performance Excellence also offer training in Lean Six Sigma, which marries lean and Six Sigma goals of reducing both waste and variation. And the University of Michigan offers a lean healthcare training and certification program.

Quick Guide to Key Lean Management Terms

Getting up to speed with lean management principles requires understanding its key ideas and terminology. Many of these come from Japan, and gaining fluency can be challenging. Here are quick definitions of some additional key terms in lean management that haven’t already been covered in-depth.

Autonomation: Autonomation, called jidoka by Toyota, most closely translates to “automation with a human touch.” It is the partial automation of tasks that humans would find repetitive or boring. Humans continue to oversee the tasks. If a problem arises in the automated process, the human operator stops the process, corrects the problem and restarts the process. This improves both quality and productivity.

Cycle time: This is how long it takes to complete one full output cycle. Understanding the components of your process and knowing the true cycle time are critical to a lean transformation.

Flow: As with rivers, flow in lean describes work moving in a steady, even stream. Lean managers aim for smooth processes, meaning a single item of work moves through an entire chain with negligible time spent waiting between steps. This concept applies both to manufacturing and services.

Pacemaker: In lean manufacturing, a pacemaker is a signal generator that alerts upstream processes to start producing. Given the lean manufacturing emphasis on pull production, the pacemaker is usually near the customer end of the value stream.

Pull: A manufacturing paradigm in which production output is determined by customer demand.

Push: A manufacturing paradigm in which production output is determined by predetermined output targets.

Takt time: The takt time for a particular product is the time in which it needs to be created to satisfy customer demand. Calculate this number by dividing the net production time available by the number of units needed to satisfy customer demand.

Value: In lean manufacturing, value is anything the customer is willing to buy, whether that be tangible (the product itself) or intangible (the prestige of owning a product, the experience of buying a product, or the quality of sales and support).

Waste: In lean manufacturing, waste is anything incurring time, financial, labor, or other costs that the customer is not willing to purchase. Japanese manufacturers described three types of waste: muda, mura, and muri. The muda category was further subdivided into seven waste types: defects, overproduction, over-processing, waiting, transportation, motion, and inventory. When companies outside Japan conceptualize waste, they’re usually referring only to muda.

Improve Lean Management Systems with Smartsheet

From simple task management and project planning to complex resource and portfolio management, Smartsheet helps you improve collaboration and increase work velocity -- empowering you to get more done.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.